The deserted cave city of Chufut-Kale

Chufut-Kale, from below |

From the khan's palace in Bakhchysarai we took a marshrutka a couple of kilometers up the valley, to the next sight. A marshrutka, by the way, is a mini-van bus, so named because it "marches along a route". We walked a good bit further up the valley on a forest path. Eventually, the forest ended, and in the open we could see the top of the cliffs, and a defensive wall. Hacked into the cliff were many dark openings, gaping like the eye sockets of a skull. Set into the wall was a gate, manned by locals asking a modest sum for admittance. We had reached the deserted cave city of Chufut-Kale.

Caves |

Beyond the gates were steep, narrow cobbled streets, flanked not by houses, as in a normal city, but tall, sheer stone walls, and cliffs with more gaping windows and doorways cut into them. The whole side of the cliff appeared to be hollowed out by man, and turned into a kind of natural apartment building. Inside, the caves were surprisingly habitable, with stone benches carved along the wall, cooking holes in the floor, and possibly storage holes, too.

"Living room" |

Some of the apartments even had two storeys, with staircases carved into the stone. And all had "window" openings admitting light. By the looks of some of the openings they must once have held wooden doors, long since rotted. Higher up is a small defensive wall dividing the upper city in two, and even further is a much bigger wall with a large, locked gate. Cave city sounds like an exaggeration, but that's really what this must have been once.

East gate |

Which makes one wonder who made it, and why. The answers are actually not fully known. What is clear is that over the centuries various peoples have taken refuge here, using the cliff as a natural protection against enemies. The tatars appear to have taken the town when they took Crimea, and used it as their initial capital, before their power grew and they felt they could safely move down the valley to Bakhchysarai. They kept the town as a fortress for some centuries before leaving it. At which point other minorities moved in.

Kenesas |

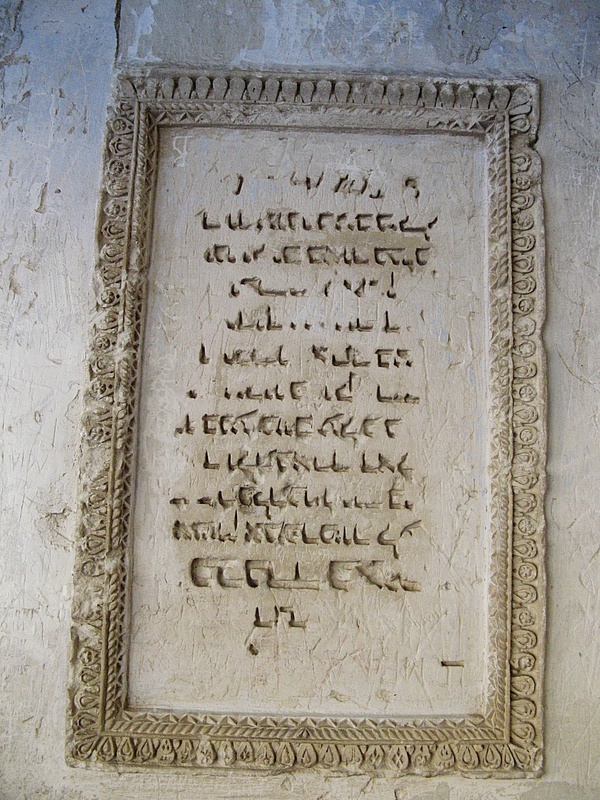

Higher up in the town are two stone houses. They stand out because they are the only actual houses in the whole town, and because they are so well preserved. In fact, they looked like they might still be in use. Carved into the rock next to them is a weather-worn inscription in what is unmistakably Hebrew writing. I stared at it in confusion. Hebrew? Here? But wasn't this place the refuge of the tatars? They wrote Arabic, as we'd seen in the khan's palace.

Hebrew inscription |

I looked in the guidebook, which mentioned "two kenassas (karaite prayer houses)". That must be these. But what are the karaites? The guidebook briefly mentions them as "a dissident Jewish sect". It was years before I found out who these people really are. As it turns out, there are several interesting stories relating to them.

To explain, we need to go a long way back, all the way to an ancient and rather shadowy realm known as Khazaria. This was a large empire to the east and north of the Black Sea for roughly three centuries from 650 AD onwards. It was ruled by a people speaking the now long-exinct Khazar language, one of many Turkic languages in this region. Remarkably, this people converted to Judaism at some point after 740, adopting Hebrew as their script and also as their written language.

Very little is known with any certainty about Khazaria, and far right extremists have concocted a number of conspiracy theories about the importance of this "Jewish empire". The exact nature of the connections between the karaim and the khazars are not clear, but both spoke Turkic languages and followed Judaism. This is less unusual than it might seem. There is in fact evidence that large parts of eastern Europe were Judaic before it turned Christian. Nearly all of this Judaic world is now completely gone together with the khazars, but the karaites still live in Crimea.

Karaite wooden house, Trakai, Lithuania |

Remarkably, at the time when much of Ukraine was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a number of karaim were invited by Grand Duke Vytautas to move to Lithuania. They made a living as bodyguards and castle guards, and about one hundred karaim still live in Trakai, beside the two ancient Lithuanian castles. Visiting Trakai to see the castles I found karaite wooden houses, a kenesa (prayer house), and even a number of cafes serving karaite cuisine. Many of the wooden houses have windows divided into three panes: one for God, one for the family, and one for Grand Duke Vytautas.

Karaite cuisine |

Under the Tsarist government there were harsh restrictions on where jews could live, what jobs they might take, and so on. The karaim led a campaign to be classified as a Turkic rather than Jewish people, on the not illogical grounds that they spoke a Turkic language. The Tsarist government eventually accepted this argument, and ruled the karaim excempt from these restrictions.

Later, the rise of the Nazis made the question reappear, this time rather more urgently. The karaites repeated their success. Already in 1934, the karaite community in Berlin petitioned the Nazis to be exempted from the laws against jews. The relevant Reich agency officially ruled that karaites were not to be considered jews. This was less of a blessing than it might seem, as in the heat of war and genocide, many karaites were mistaken for jews and murdered all the same. Today, very few are left, and even fewer can speak karaim.

Middle defensive wall, Chufut-Kale |

Clearly, life in 17th century Crimea had not been without its dangers, either, as the massive walls and fortifications of Chufut Kale testify. Interestingly, the name is tatar, and means "Jewish rock", in a highly derogatory sense. So the Turkic tatars have clearly looked down on their Turkic karaite neighbours, and considered them jews. The logic of racism is a tangled, confusing thing.

Mesa |

The road lead higher up from the kenessas onto a kind of open plateau. From here we could see that the long, flat top of the cliff must continue for a good distance. Across the valley was another cliff, looking very like a Texan mesa. A single building stands in this area: the mausoleum of the daughter of one the khans.

Mausoleum of Dzhanike-Khanym |

We poked around, climbing into the bigger caves, exploring the streets and walls. Many of the streets have grooves worn in the stone by the passage of carts. In some places these are very deep, showing that the city must have seen considerable activity over hundreds of years.

Wheel ruts |

Exploring all this was an odd feeling. I'm used to ruins having roped off areas, signs, guides, maps, and lots of tourists. Tourist attractions are supposed to be fenced in, packaged, and presented to the visitor, but here it was just us and the rocks. We could go where wanted, see and do what we wanted, and there was nobody to disturb us. Also, there was nobody to answer my questions.

Eventually, we left, walking down the valley to the marshrutka that took us to train station.

Bakhchysarai train station |

Similar posts

Bakhchysarai

We took the elektryushka, the electric commuter train, out of Simferopol, through the lovely Crimean countryside

Read | 2014-03-09 12:35

The Norwegian Topic Maps market

My boss, Ole-Jørgen Tallaksrud, wrote a short summary of the state of the Norwegian Topic Maps market on request for someone writing a grant application for a research project

Read | 2007-10-04 09:45

Comments

No comments.