Farmhouse ales of Europe

Farmhouse brewing, Kaupanger, Norway |

Having surveyed the state of farmhouse brewing in Norway it's time to look at the same thing in Europe generally. The last time I did that was four years ago, but I've learned so much in the meantime that the picture looks completely different this time around. The most surprising thing about it is how much of the farmhouse tradition that is actually left, and how incredibly little known it is.

Some people seem to equate farmhouse alge with saison, but there is a lot more to it. Every place that still has a living farmhouse tradition has a beer style of its own that is completely unique, and several of these regions have more than one. And when I say "completely unique" I mean that literally. The spread in flavours and techniques is enormous. Many of these brewers do things that no modern brewer would ever dream of doing, and they're all different from one another. So if you feel like you've tasted all the different kinds of beers there are and there's nothing new any more, well, read on.

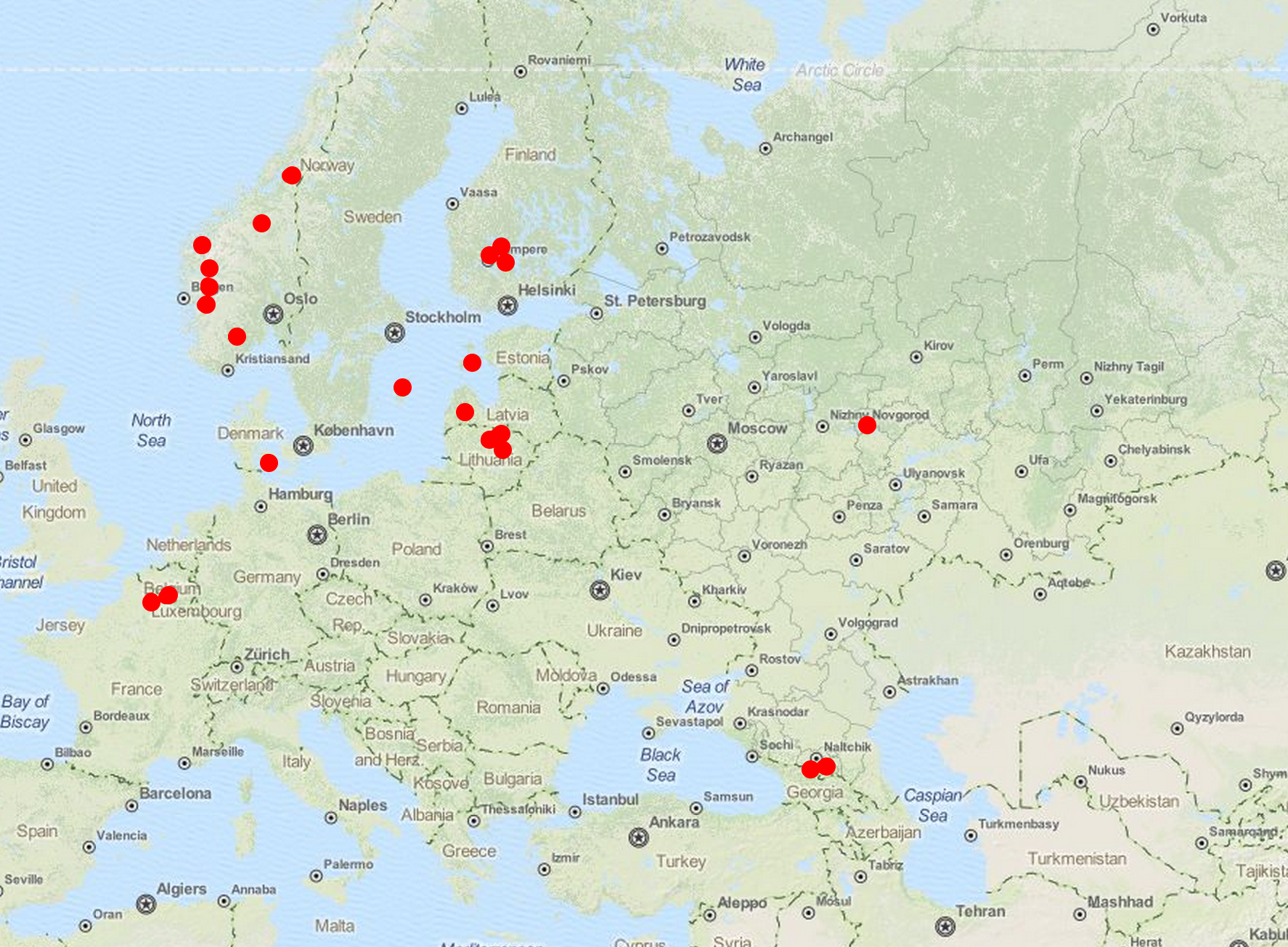

On the map below I've marked the places where I know for certain that the farmhouse tradition still lives. You can see right away that the regions have something in common: they are primarily agricultural and fairly remote from capitals and major industrial areas. I also get the impression that to preserve its farmhouse tradition, an area needs a certain minimum number of inhabitants. Thus, the smaller European islands, and the truly remote and isolated areas have lost their traditions. Unless I've missed something, which is entirely possible.

Farmhouse regions |

I'll start with the edges of this map, and then we can zoom in on the central, northern cluster of regions.

Belgium and France

This area is so well known there's hardly any point in writing about it here. It's also very different from the other regions in one key way: farmhouse brewing here seems to be mostly, or maybe even all commercial. As far as I know, traditional home brewing has died out, but it's left a commercial legacy that means at least some form of the traditional beer still exists, and it's widely available.

Georgia

Mural of Georgian landscape, from a restaurant in Kiev, Ukraine |

Georgia is much better known for its wines, which were famed throughout the whole Soviet bloc. It turns out, however, that high up in the Caucasus mountains you cannot grow grapes, and so the people there brew beer instead of making wine. Specifically, these customs seem to live on among three ethnic Georgian minorities: the Khevsurs, the Pshavi, and the Tush, all of them living in remote mountain regions. The beer is woven into their social customs, with some of it being brewed for religious events and rituals, and in other cases for other customary purposes.

Unfortunately, finding solid information about these beers has proved very difficult. I've established that it's brewed in big copper cauldrons, from barley or wheat, and that they use hops, water, and yeast. The hops must be acquired from the plains, one source wrote, but said nothing about doing so with the yeast, which makes one wonder whether native yeast might survive there. Another account of the brewing describes the mash being boiled for several days (!?), resulting in a "sweetish, rather insipid, turbid" beer. That one was brewed with local wild hops.

Several sources write about the beer as though it no longer exists, but it's very clear that it's still being brewed. Some of these regions seem very far removed from modern life. To reach Tusheti, for example, you can drive, but only for a short period in summer, when the snow has melted. You have to use a 4-wheel drive jeep, but driving yourself is not recommended. You should instead hire a driver. The alternative is standing in the back of a Soviet-era truck over the pass for 9 hours, in freezing cold at the top. There seem to be guided tours to some of the less inaccessible regions.

So is this beer any good, or is it just a primitive grain soup? I have no idea. Georgian cuisine in general is absolutely fantastic, so who knows. One source described it as brown, and clearly did not like it, but didn't say anything more. Another (from 1878) also describes the beer as brown, then adds that it's like Bavarian beer (?!) but "imperfectly clean". It's difficult to know what to make of this, really.

(I'm deeply grateful to Ben for the tip about Georgian beer, and pointers to useful sources.)

Russia

Russian pub, in Moscow |

I've wondered for a long time whether the Russians might not have brewed things other than kvass and vodka, and whether some remnant of this tradition might not have survived. Russia is, after all, peopled with many ethnic minorities and splinter groups, distributed over an enormous area. In a country where a family can live for 40 years without contact with the outside world, could not a brewing tradition survive even 70 years of communism?

And then one day, I found an account of brewing traditions in the Russian Empire. And there it was: "The best cereal drink of the Russians was beer. It definitely belonged in every party and great amounts were brewed." (My translation.) The book then went on to list the brewing traditions of no less than 12 different ethnicities. Googling one of them, the Chuvash, I hit gold.

It turns out the Chuvash people, living on the middle Volga, between Nizhniy Novgorod and Kazan, have kept the farmhouse brewing tradition alive. It cannot be a coincidence that the Chuvash Republic, the district in which they live, is the main hop growing region in Russia. From the description in the book, clearly they brew beer from barley (sometimes also oats, rye, or wheat), malts, yeast, and hops. There's even a video showing farmhouse brewing in the region in 2002.

One thing that struck me about this is that while farmhouse brewing is incredibly varied, a century ago beer was brewed from the same main four ingredients (barley, hops, water, and yeast) over an enormous area. If hops really were first introduced into beer around the 9th century, how come it spread so widely and so completely in just a millennium? (Actually, probably faster. There's evidence that Muscovy had a substantial hop trade already in the 17th century.)

From France or Germany to middle Norway, northern Finland, Georgia on the south side of the Caucasus mountains, and Chuvashia on the middle Volga is an enormous area. That's a very, very impressive spread, and a story that requires some explanation. (I'm not saying it's wrong, just that it's startling. These people all speak different languages and make totally different foods. So how come they all make beer from the same four ingredients?)

Note that it's likely that farmhouse brewing has survived elsewhere in Russia, too. So far the evidence for it is missing, but it may one day turn up.

Zooming in

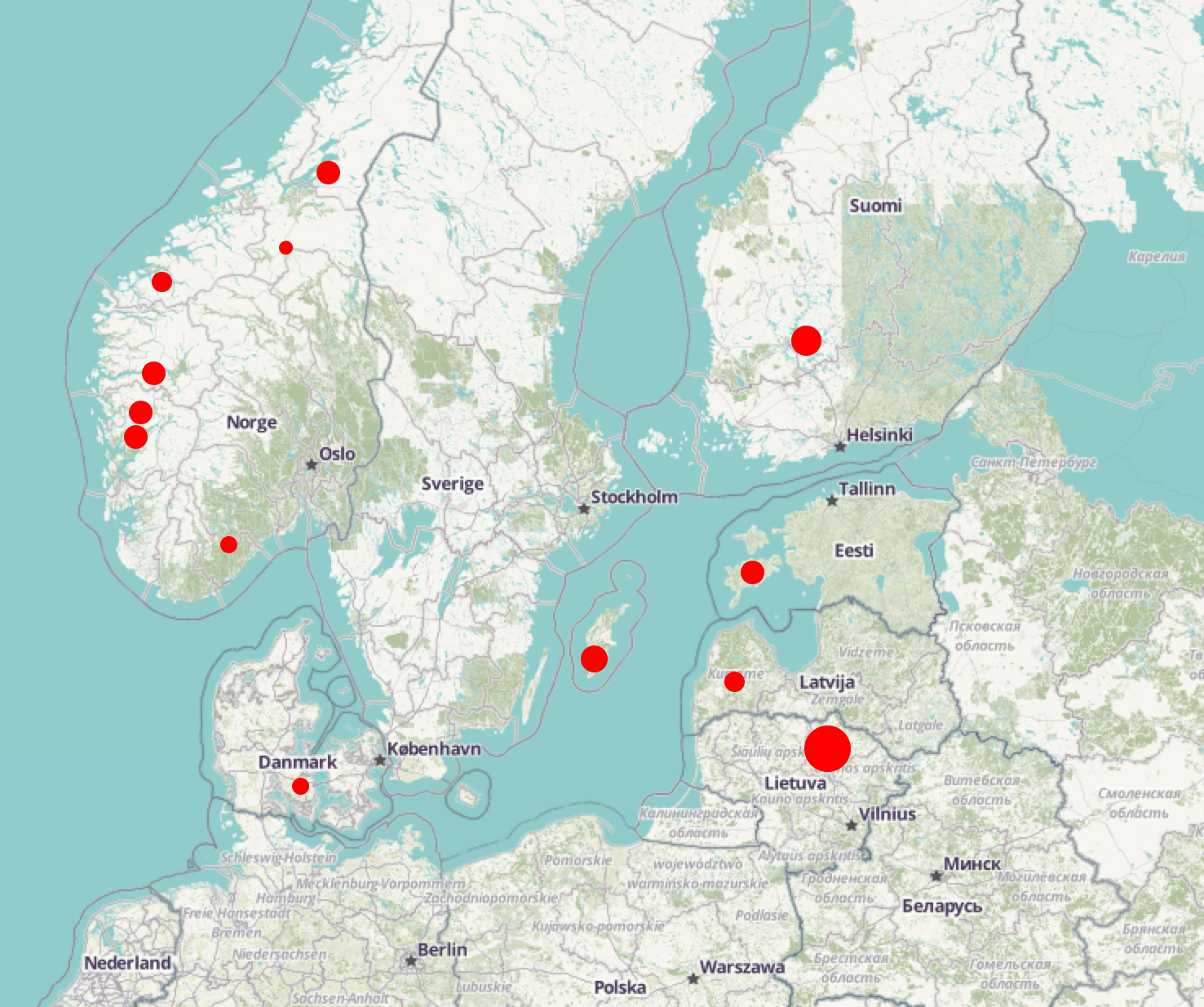

Having covered the periphery, as it were, it's time to take a closer look at the north-western corner of the first map. So let's zoom in a bit:

Northern farmhouse regions |

As you can see, we've only just started going through the farmhouse traditions. I'm afraid this is going to be a long blog post. I'll keep it as short as I can.

Denmark

Danish farms |

In Denmark the farmhouse tradition survives, just barely, in the southern part of the island of Funen. The ingredients were the usual: barley malts, hops, water, and yeast. A very brief summary of a pre-WWII survey describes a raw ale (that is, from unboiled wort), fermented with home yeast, pitched at about 35-37C, with hop tea boiled on the side. Where they got the malts and hops from is not described. There are more details, but that gives the basic idea.

I have a single description of farmhouse brewing on southern Funen in this millennium. That describes a boiled ale made with brown sugar and lager yeast, as well as commercial hops and malts, by a woman who had really stopped brewing, but was willing to do it again just to show the author. How much actually survives in this area is unknown, but probably not that much. It's probably safe to say that Danish farmhouse ale is barely hanging on, if at all.

Norway

By comparison, Norway has a booming and growing farmhouse brewing culture, spread out over several styles and several geographical areas, as covered in the previous blog post. The brewers here make what is called "maltøl". The family yeast lives on, as do native hops, malting traditions, raw ale, and much more. One thing that really distinguishes the Norwegian tradition from the ones described above is the heavy use of juniper. Juniper infusion is used for all purposes in the brewing that would normally involve water, and this has a major effect on the flavour in most regions. What is especially noteworthy is that some of these beers are very, very good.

Sweden

Old Town, Stockholm |

Farmhouse brewing died out in Sweden in the 19th and 20th centuries, but still survives on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. The beer brewed there, known as Gotlandsdricka, is relatively well known by now. There are lots of farmhouse brewers on the island today, and they even have an annual competition, known as the World Championship in Gotlandsdricka.

The brewers make their own smoked malts, but they buy bread yeast and hops from the supermarket. As in Norway, juniper infusion forms the basis of the brew. They mash for two hours, add a little white sugar, then boil it. From the basic description I have it sounds very similar to the Norwegian stjørdalsøl.

Finland

Of all the farmhouse ales outside of Belgium/France, the sahti is by far the best known. It's often described as "the oldest continuously brewed beer style in Europe," but as this blog post should make very clear, that's nonsense. It's usually thought of as a single beer style, but should probably be considered an umbrella term for several styles, just as with Norwegian maltøl. There are some sahtis that sound very like Norwegian vossaøl, but there are also raw sahtis. There was also widespread use of hot stones in a number of creative ways that I never heard of any steinbier brewer using them.

Juniper is used, but not as heavily as in Norway and Gotland. For the rest it's barley (with rye or oats if necessary). The brewers do a step mash, which is unlike Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. As in the other areas described above, the yeast was originally home-owned, but today everyone seems to use bread yeast.

Today the tradition lives on in a relatively large area to the east and north of Tampere. There seem to be many brewers, and commercial varieties of sahti have been easily available in Finland for a couple of decades. How true to the original style the commercial variants are I cannot say yet. Certainly the commercial ones are unique in flavour, and totally unlike anything else I have ever tasted.

Estonia

Modern recreation of medieval beer, Tallinn, Estonia |

Moving south into Estonia we reach an area that as far as I know has barely been described in English at all. Farmhouse brewing used to be common in all of Estonia, with considerable variation, but now seems to only remain on the island of Saaremaa. I'm not going to go through all the historical variations of Estonian farmhouse ale, but suffice it to say that what remains is just one of several styles.

The koduolu of Saaremaa is generally made from home-made malts and locally grown hops. Juniper seems to only be used in filtering. As far as I can tell it's a strong, raw ale. An iron flavour from the iron in the groundwater is another feature. There are hundreds of brewers, and as on Gotland they have an annual competition where you can taste lots of different koduolu.

At least one commercial variant exists, and several sources I respect described it as both very good and very interesting. Here's the Beer Trotter's account. Apparently this beer is now also available in Tallinn. A report on the brewing of koduolu from 1995.

Latvia

Wooden house, Riga |

Latvian farmhouse ale still lives, but as far as I am aware, the only existing English documentation of it is an email I got in 2012. The style (or styles) must have a name, but I don't know what it is. I'm not even sure where in Latvia the brewing survives. The few clues I have point at the town of Aizpute, in western Latvia. Two Latvian reports from gatherings to recreate the beers: 2010 and 2011.

As far as I can tell, the ingredients are home-made malts, wild hops, and bread yeast. However, older sources describe a raw ale made primarily from barley malts and mashed with hot stones sprinkled with flour. Apparently juniper infusion was much used because people liked the flavour, but for stronger beers people might use Myrica gale or even tobacco. People had their own yeast, which was reused from brew to brew. Another method is also described, sounding very like Lithuanian keptinis, where bread is baked from malts, and then used in the mash.

Lithuania

Wooden brewery, Dusetos, Lithuania |

I've worked for a while on documenting the Lithuanian farmhouse tradition of brewing kaimiškas. After studying this for about four years now I feel confident in saying that in beer terms Lithuania is by far the most interesting of all of these regions (except Belgium). One thing is that the farmhouse tradition is better preserved here than anywhere else, but it doesn't stop there. Like the Belgians, the Lithuanians have developed a commercial brewing culture from their farmhouse traditions. The result is a commercial brewing culture totally unlike any other. So in Lithuania you can easily buy both true farmhouse ale, and also commercial beers in styles unique to Lithuania.

As for the beers, there is an enormous variety. There are raw ales and boiled ales. There is local malts, beers made with local wild hops, and even several strains of home yeast (kveik) used in commercial brewing. Plus there are traditions for using a whole host of other ingredients in the beer, such as raspberry stems, red clover, etc etc etc. There are even special styles like keptinis, brewed from malts baked into loaves.

Conclusion

In short, farmhouse ale lives in many more places than people have been aware of, and it's highly possible that this list is not complete. For example, the Balkans seem to have a tradition for a style called boza, which doesn't sound that promising, but it's quite possible they have more styles. Russia might have more, and it might survive in other regions, too.

One thing that is really striking is how widespread the raw ale is, particularly given that it's so incredibly little known. And yet not long ago it was brewed (at least) in Norway, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. I'm sure the list is longer, but those are the countries I have evidence for right now. And except for Denmark it still survives in all those countries.

As should be obvious, this is a very, very short summary, skipping many interesting details and variations. My research into this is also only beginning. I've collected a whole host of sources covering most of these regions, but coverage of Russia, Latvia, Estonia, and Georgia is still very spotty. Some of the material goes into considerable depth. I plan to slowly work my way through that, and I'm still collecting more sources. In addition, there will have to be more field trips like the Norwegian one this year and the Lithuanian one last year. So this is only the beginning.

Light from steamy brewhouse, Kaupanger, Norway |

Similar posts

Maltøl, or Norwegian farmhouse ale

This seems like a good time to summarize what I've learned about Norwegian farmhouse ale during and after the May trip

Read | 2014-10-11 13:20

Norwegian farmhouse ale

It's a well-kept secret that in Norway there exists a homebrewing tradition completely separate from the modern homebrewing that's taken off in the last few decades

Read | 2013-10-27 13:24

What counts as a farmhouse ale?

The most common question I get in interviews is "what do you consider to be a farmhouse ale?" and since the answer is a little involved I decided to write it up more fully

Read | 2020-07-26 14:52

Comments

Dave Bonta - 2014-10-24 20:42:50

Fascinating stuff. I do hope you'll consider compiling your research into a book someday. I think there would be huge interest in the American brewing community.

Lars Marius - 2014-10-25 04:45:28

@Dave: Thank you. I am pondering my book options, but very likely there will be something published.

Smetana - 2014-10-26 11:12:55

Hi,

We've just published an article on sahti. I hope you like it :)

http://smetanafi.wordpress.com/2014/10/26/sahti-the-finnish-farmhouse-ale/

I definitely agree on what you said about sahti being an umbrella term for a category of beers. The colors and strengths of sahti vary considerably, so categorization under the modern beer rating terms into a single type of beer is not accurate.

Lars Marius - 2014-10-26 11:15:30

@Smetana: Excellent piece, and great pictures! I'm adding your blog to my RSS reader right now.

Martyn Cornell - 2014-11-04 20:21:11

I would love to go to Chuvashia one day ...

Interestingly, the Georgian for "beer", ludi (aludi in mountain dialects) is reckoned by linguists to be part of the ale/øl/alus/olut family, though how the word got from Northern Europe to the Caucasus is unclear.

Lars Marius - 2014-11-05 14:14:41

@Martyn: At the moment it looks like the field trip to Chuvashia will be in either 2017 or 2018...

For Georgian to use an Indo-European term is interesting, given that Georgian belongs to an isolated language family. It really suggests outside influence, even if it doesn't prove anything.

Chuvash is a Turkic language, and apparently their term for beer is "shara". None of the other beer terms I saw suggest Indo-European influence, either.

Martyn Cornell - 2015-01-08 04:53:06

Georgian linguists believe the word for beer probably came to their language from their neighbours the Ossetians, who are the descendants of the Alans, who themselves ranged widely over Europe (and as far as North Africa) in the age of the barbarian invasions and could have picked up the "ale" word from eg the Vandals or other Germanic speakers.

The general old word for beer in Turkic languages appears to be sıra, which looks to be the same as the Chuvash word. Let me know how arrangements for the Chuvashia field trip go - I'd love to join it.

On the subject of "raw" ales, of course, if you don't use hops, you don't need to boil, and I'm sure all pre-hop ales were "raw". Certainly even in the late 17th century in England one self-styled expert was suggesting that brewers ought not to boil their worts.

The boza tradition, incidentally, spreads right down into Egypt - that Wikipedia article doesn't cover the half of it. Here's an abstract from an article published in 2002:

"Boza is a traditional Turkish beverage made by yeast and lactic acid bacteria fermentation of millet, cooked maize, wheat, or rice semolina/flour. The name, boza, in Turkish comes from the Persian word, buze, meaning millet. However, the Turks who lived in Middle Asia called this beverage bassoi. There are also similar beverages produced in East European countries (braga or brascha), the Balkans (busa), and Egypt (bouza). In the past, boza has been produced and consumed with slight differences in the recipe in the Turkish countries. Boza is made of various kinds of cereals (usually millet, maize, and wheat), but boza of the best quality and taste is made of millet flour. In the Balkans, such as Bulgaria, cocoa is also included in the boza recipe. Boza produced in Egypt has high alcohol content (up to 7% by volume) and is consumed as beer. Because of its lactic acid, fat, protein, carbohydrate, and fiber contents, it is a valuable fermented food that contributes to human nutrition."

Morten - 2016-08-22 22:17:32

Hi Lars I am very interested in digging more into Danish farmhouse ales.

Can you refer me to your source of these pieces: ".... A very brief summary of a pre-WWII survey...There are more details, but that gives the basic idea....I have a single description of farmhouse brewing on southern Funen in this millennium......but was willing to do it again just to show the author."

Thank you for your enthusiasm and interest in keeping our roots alive

Morten

Lars Marius Garshol - 2016-08-23 02:40:13

Hi Morten,

Sorry to be so obscure about the sources, but I didn't want to blow up the blog post to 3x the length it has now by including all the sources.

The survey summary can be found in Ømålsordbogen, Universitets-Jubilæets Danske Samfund ; Københavns Universitet, Afdeling for Dialektforskning, under the entry for "brygning."

The other source is Alle tiders øl, Per Kølster, Politikens forlag, Copenhagen, 2007. ISBN 9788756776165. An excellent book, which I really recommend.

See also this blog post: http://www.garshol.priv.no/blog/334.html

Sandro Shanidze - 2020-01-22 11:32:13

Hello, I realize that this is an old conversation I intend to join, but I hope the topic is still relevant. My name is Sandro Shanidze, I'm a hobbybrewer from Georgia, the country, while also being a PhD student at the Agricultural University and though my specialty here is not yeast, I have started to use my access to the lab to experiment with isolating local yeast strains. I had known your blog by reading about kveik, but know I came here again after searching if there are English-speaking sources on the beer traditions in the highland Caucasus. I am also very interested in the history of beer and would like to add something that people have commented here: The Georgian word for beer - 'ludi' also 'aludi' in the dialects of highlands neighbouring North Caucasus comes from the Ossetian word 'ælut' which, the Ossetian being a descendant of Alan, Scythian and an Indo-European language, comes directly from Proto-Indo-European word h₂elut- related to brewing, and so these words have a common origin like the English ale and Norwegian øl.

This information is available on English wiktionary: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ლუდი

Georgia is a wine-country, being one of the oldest places of vine domestication - but the highlanders, who can't grow vine but grew barley on mountain-slope terraces, brew beer, something that following the linguistic evidance - was practiced by most of the peoples of this highlands, who today practice Islam, like the Chechen-Ingush peoples and Karachay-Balkars. The Ossetians are an exception - they have never stopped brewing beer, being mostly Christian (Eastern Roman, Byzantine influence) and having no taboos regarding alcohol consumption, beer is the sacred drink in Ossetian traditions. The ossetian culture is a mix of local, Caucasus highlander culture and the culture of their (at least linguistic) forefathers, the Scythians, who have historically roamed the vasts of Eurasian steppes and have been brewing beer there, which has to have common roots with the Chuvash beer traditions you have written about. The Chuvash speak turkic, but their culture has a substrate that is older than the arrival of Turkic nomads in Volga area and that substrate has deep roots connected to some ancient beer-brewing traditions of that region.

I think the Ossetian beer tradition is something you might be very interested in. I can't offer you any help with a tour there, out of political reasons, but if you were to travel to Ossetia, I would be happy to invite you to Georgia, where we too have some traditions of highland-beer brewing and which I am in the process of studying on hobby-level. If you come to Tbilisi, there is a nice Ossetian microbrewery here attached to an Ossetian restaurant, they brew something like an old ale style, one of the tastiest for me =D

I hope to have kindled some interest in you, I would love to assist you to popularise brewing traditions of the Caucasus.