Mead: a Norwegian tradition?

Polish meads |

Most people think of the vikings as big drinkers of mead, and believe that Norway has a long and strong tradition for mead-making. I used to think the same, until I started looking into traditional farmhouse brewing. There were lots of descriptions of how people brewed on the farms all over Norway, but nothing at all about mead.

Of course, just because nobody wrote about it didn't mean that it didn't exist, and this is where the ethnographic survey on farmhouse brewing came in handy, because questions 99 to 103 dealt with mead. Here people were asked straight out: did people in your area make mead, or did they not?

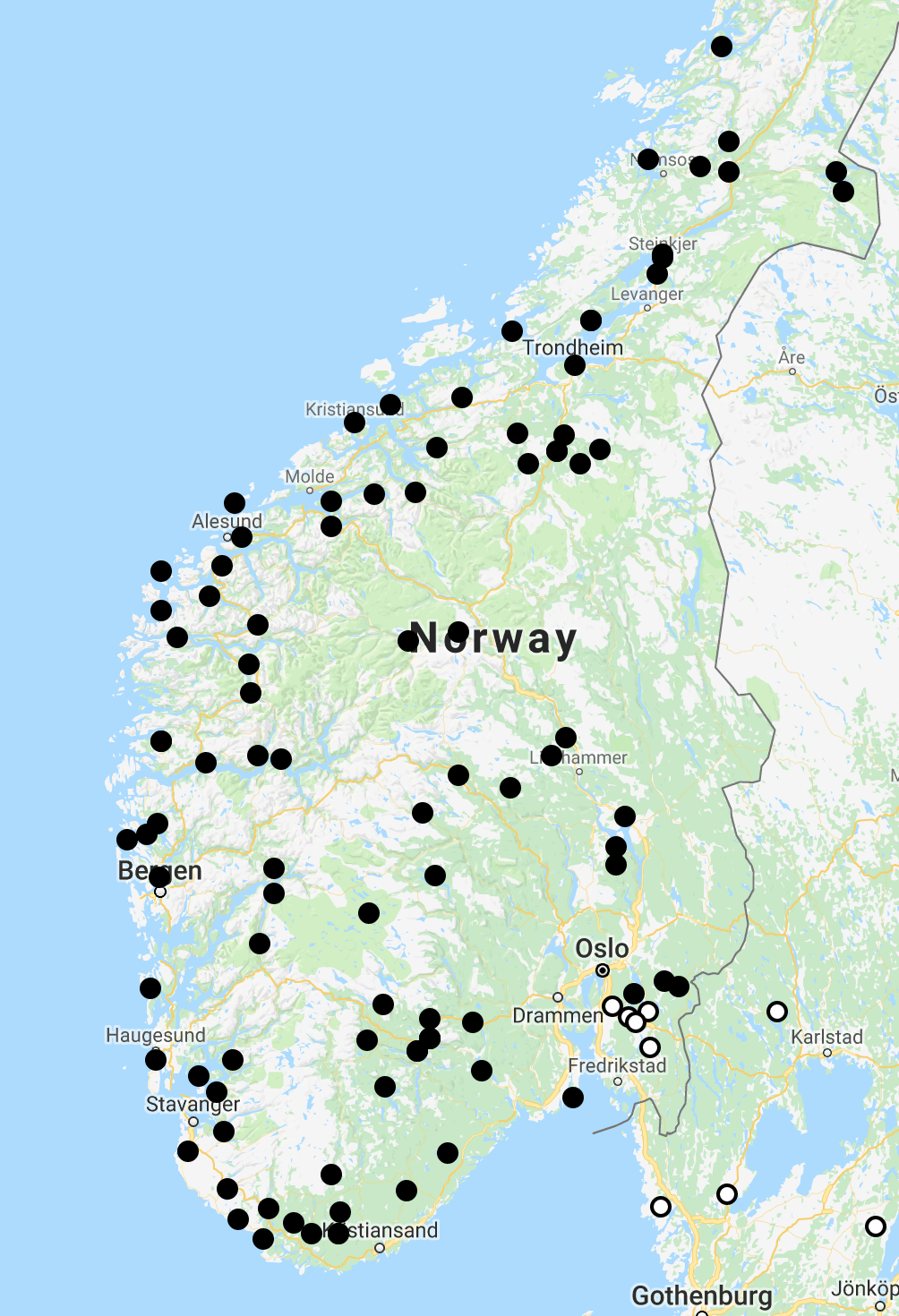

The results are brutally clear: from village after village after village people write: "I know nothing about this." "Never heard of anyone making mead." "There is nothing to tell." "Some people might buy it in town before Christmas." Except it wasn't quite that black. I plotted the answers on a map to get a clearer picture, and the result is quite startling.

Black = no mead, white = people made mead |

Five out of well over a hundred answers report mead-making, and they form a very clear-cut geographic cluster. This had to mean something, but what? (There are no black dots in Sweden because the Swedish questionnaire isn't phrased so that people respond: "No, we didn't make mead here.")

The replies themselves were pretty clear. Four out of five say that people who kept bees sold the honey, then made mead from the honey that remained, stuck to the wax combs. They would dissolve the honey in hot water, boil it, add some spice, and ferment it. One answer says people collected wild honey.

There's no doubt that the answers are correct. These people are describing what took place in their own home villages, and five of them independently agree with each other. So people did make mead here. But what about the rest of Norway? Did they once make mead and then stop? If so, why would they stop there, but not in the south-eastern corner (Østfold)? It took me a long, long time to get any further on this.

Foraging bee, Hovedøya, Oslo, Norway |

There are a few 18th century topographical accounts of various places in Norway. Two that deal in detail with beer brewing from Telemark and Nordfjord say nothing about mead. The one from Spydeberg in Østfold, however, does describe bee-keeping and mead-making [Wilse 1779]. So clearly the tradition at least dates back to the late 18th century.

I knew what I needed was serious literature on bee-keeping, and that took a while to find, but eventually I bought Eva Crane's massive tome on the subject, and dug in [Crane 1999]. And it was like turning on a light switch. Her map of the native distribution of honey bees shows their range ending just south of Norway. A more detailed map later shows that theoretically they might be able to survive in the south-eastern corner, just around Oslo, and a little ways down the western side of the Oslo fjord. In theory.

The problem is not so much the cold, as the short duration of the flowering season. The bees live from pollen and nectar, which they collect while the plants are flowering, and make honey from them. The honey is used to rear infant bees, and also as an emergency food supply for the hive. But far north the flowering season is too short, and the bees basically starve to death before the next season begins.

Traditional beehive, Lithuanian National Museum, Rumšiškės |

Inspired, I went back to [Wilse 1779] and looked at it again. The very first sentence on bee-keeping says: "One doubts no more that bees can be kept in Norway." No more? So people did once doubt it? He then quotes page 504 of an earlier book, by justice councellor Fleischer, on bee-keeping. I never managed to find that, but I found a letter from Fleischer, written in 1745 [Fleischer 1745].

The letter says "Bee-keeping is not known here (that is, south-eastern Norway)." Many have tried, he says, but the bees die in winter. "One thing is that the air and this climate are too cold, another is that one doesn't understand how to do it." Going back to Wilse the picture clears. Wilse describes how someone in Oslo managed to succeed with bee-keeping in 1740, and that bee-keeping has spread.

Wilse himself got a bee-hive in 1774, and had been keeping the hive since. The problem with the bee-keeping (Wilse says) is that the bees awake too early in spring, while there is still snow on the ground, and go out searching for flowers, and die in thousands in the snow. He's managed to avoid this by closing the hive with a perforated metal plate, and feeding the bees with watered-down honey.

Suddenly it's clear that what's going on is exactly what Crane described. The bees run out of honey and desperately go searching for food, even though it's too cold outside, because it's either that or starving to death. And then they freeze to death. But by feeding the bees through this period they can be kept alive until there is food for them to find.

Beehives, Stockevik, Sweden |

So bee-keeping seems to have begun in Norway in the middle 18th century, specifically in the south-eastern corner. It seems to only have developed a strong tradition there, where the climate was suitable for bees. The local mead-making tradition then grew out of this.

But what about the vikings, then? A find of "tens of thousands" of dead bees from 1175-1225 in the Old Town in Oslo has been made [Crane 1999], which probably shows bee-keeping. This is toward the end of the Medieval Warm Period from ca 950 to 1250, so perhaps people did keep bees in at least part of Norway then, and later lost the knowledge when the climate became too hostile for bees.

Probably this bee-keeping was never very widespread, but the vikings were famous traders and raiders, and very likely bought and/or plundered honey abroad. We know that wine was traded from the Mediterranean up to Scandinavia back to the year 0, and probably also before. But the supply of wine and mead must have been very, very limited.

Mead is relatively prominent in Norse mythology. In the sagas, which claim to be stories what people actually did, there is less mead. In Egil's saga there is a mention of someone sailing to Denmark to buy honey (among other things), which fits well. There are other mentions, too, but mostly people seem to drink milk and beer. It's clear from the surviving literature that wine was considered the finest, then mead, then beer. And what was finest was so considered because it was the most expensive, and the most rare, of course.

I'm no expert on Norse literature, but overall, it seems safe to conclude that while the vikings did drink mead, that was a rare luxury, and that the Norwegian bee-keeping and mead-making traditions are fairly recent.

Sources

[Crane 1999] The World History of Bee Keeping and Honey Hunting, Eva Crane, Routledge, 1999. ISBN 0415924677.

[Fleischer 1745] Beskrivelse over Det Smaalehnsche Amt, Baltzer Sechmann Fleischer, Østfold historielag, 1985.

[Wilse 1779] Physisk, oeconomisk og statistisk Beskrivelse over Spydeberg Præstegield, Jacob Nicolai Wilse, Christiania, 1779.

Similar posts

Polish mead: nectar of the gods

Before going to Poland back in 2007 I checked Ratebeer, as one does, to see what the best beers from Poland were

Read | 2014-04-29 19:52

Nordic grog

The origins of beer brewing in Scandinavia are lost in the mists of pre-history, and today we have very little evidence of how it began

Read | 2015-02-09 20:44

The juniper mystery

When I started looking at farmhouse ale back in 2010, one of the first things that struck me was that nearly everyone seemed to be using juniper

Read | 2017-02-02 09:43

Comments

Misha - 2018-04-15 20:50:01

A couple of little "tweaks" to the tale, since I'm a beekeeper, as well: Yes, the flowering season that far north is too short. Likely, the vast majority of flowering/nectar-producing plants are mainly trees, and are finished up fairly early in the summer. But the bees aren't "flying out in desperate search for food;" if they manage, somehow, to store up enough nectar (honey) and pollen to carry them through to the next spring, they'll be fine. Rather, things probably warmed up *just* enough for them to start doing "cleansing flights"--near 50 degrees F, immediately near the hive. (Bees won't "relieve themselves" inside the hive; they fly out to do that.) Once they're a little bit away from the hive, it's too cold, and they chill. Happens even here in Maryland, in late winter/early spring. (If you go out and carefully pick them up, they'll "come back to life" in your hands, from the warmth...) And the bees actually feed the brood with pollen, not honey. Honey is for mature bees... But the eggs/larvae need protein, which is in the pollen. Cheers! --Misha

Marc Graham Dineley - 2018-04-16 09:31:04

Lars, Svein Asleifarson drank mead when he could steal it from English shipping (Orkneyinga Saga). The topic of mead crops up so often in prehistoric "alcohol production" that I wrote a blog about it: http://merryn.dineley.com/2014/06/ale-or-mead-numerical-and-functional_9.html I came to the conclusion that mead is a Saxon literary tradition, and that in reality it was only for poets, kings and gods, not mortals. Cheers-- Graham.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2018-04-16 09:37:35

@Misha: Thank you for the corrections! I'm not a bee-keeping expert.

@Graham: Yes, I read that blog post, and it's one of the things that put me on the path to writing this blog post. I completely agree with your conclusions.

Fredrik Stai - 2018-04-16 10:58:28

Thanks for an interesting read, Lars! Looking forward to see if you're able to dig up more about the history of mead making in our corner of the world. I've shared the article on a Facebook group for Norwegian beekeepers and encouraged those who know anything to comment here. If you're looking to do more research, it could be worth talking to Roar Ree Kirkevold, who has the biggest collection of books on beekeeping in the country. There's the chance that he has come across some useful info in one of his books.

I'm a beekeeper myself and live in the area with white dots. Misha's corrections are correct :) With one exception: we're far from limited to trees. The main honey flow in Norway is raspberry, and it's a big one in many parts. Salix is important in the spring. Then comes tussilago, blueberry, maple & the various fruit trees, dandelion, raspberry, clover, linden… to mention some common ones. And last but not least: heather in the autumn.

Heather honey actually becomes a challenge to honey bees during the winter, since it basically causes bee diarrhoea when it's too cold to leave the hive to take a dump, leading to a spread of diseases which is likely to make a colony perish by the time spring comes around. So where heather is present, it's an obstacle to wild honey bees settling down. That, and the limited amount of trees with big enough cavities to build up a big enough colony to survive the winter. So I doubt there are any real 'honey bee forest' here. No truly wild honey bees in that sense. What we do have are a few escaped colonies that survive on their own in barns, attics and such – some of them for a decade or more. Typically they die out every now and then, but a year or two later they're replaced by an new escaped swarm from a local beekeeper.

Dan - 2018-04-16 13:50:06

Thanks for another interesting post! After having read most of the sagas and also systemized them, I say Amen to your conclusion! Honey and mead was a luxury product for the richest people in the Norse society. The problem is that it is the culture of the rich that we find in the graves and in the literature, so people think that everyone lived like that.

Alex - 2018-11-22 15:55:32

From what i read, historically as far as Scandinavia is concerned Denmark was rich in beekeeping and bees thrive well also in Skane.

Craig - 2021-07-25 04:45:44

Viking culture, as well as some of its most noteworthy literature, was perhaps just as prevalent in Denmark, one of the four countries that comprise Scandinavia. Denmark is further south than the other Viking areas like Norway, and I suppose ostensibly fine for beekeeping and mead production. Perhaps more research can be done to quantify mead production in ancient Denmark. Thank you.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2021-07-27 09:29:01

@Craig: Yes, in Denmark it would be possible to keep bees, and I'm sure people did. There is an archaeological find of mead from 1400 BCE on Zealand. Honey production will have been low (simply because it always is), but I'm sure they've made some mead.