A brief stop in Stranda

Norddalsfjorden, seen from outside Stranda |

We knew there were lots of active farmhouse brewers in the Sunnmøre region, but since we had great difficulties getting in touch with them, other parts of the trip expanded, eating away at the available time. From Flåm to Stranda is a 5-hour drive, and onwards to where we were staying next is an 8-hour drive. So in the end we had just an evening for this whole area. Which is a crying shame, but there was nothing to be done about it. (This is part 6 of the Norwegian farmhouse ale trip.)

Our contact, Stein Langlo, has been central to the local home brewing community for some decades now. I'd spoken to him on the phone a couple of times, and he'd agreed to meet us so we could taste a few home brews. Stein met us at a local restaurant, then took us to his car. I was in the passenger front seat, and was surprised to see that I was sitting next to a box of sour cream, stuffed into the side pocket of the car door. "Strange," I thought. "Who drives around with sour cream in their car?"

As we drove around and were shown Axel Springer's cabin, olivin mines, the fjords, etc, I kept asking questions about local home brew. Stein's answers were kind of brief, as though he were still not sure of us. But when I started talking about kveik, analysis at a yeast lab and so on, he reached down next to his seat and gave me a sour cream box. "Here," he says. "Take it." Confused, I open it, and find lots of hard, gray flakes.

The kveik (transferred to a glass jar) |

"Taste it," Stein says. I do, and immediately recognize the taste from childhood. It's dried yeast. It dawns on me that I'm being given another sample of kveik. "There's another one on your side," he says. So I open the sour cream box on my side, to find the same thing there. The contents of the two boxes smell clearly different. I try asking why, but never get a clear answer. (Analysis at NCYC is still ongoing because they are having difficulties getting the yeast to grow. More on this later.)

Then Stein takes us to his warehouse, where he keeps imported malts, hops, yeast, equipment, and other homebrew supplies. He has a small business selling this to local home brewers, and also sells to small breweries and brewpubs in the region. He's even helped some of them get set up and delivered their equipment complete with training.

Sosialen |

Next we go to his own brewery, which has a sign above the door, saying "Sosialen" (The Social). It's aptly named, as it's a communal brewery used by a group of friends who also go hunting together. The equipment is by now deeply familiar: an iron kettle heated by wood fire. He's made his own mash tun, with a steel grating in the bottom, and insulation tape around it. So far, so traditional, but then he shows us a refractometer, for measuring sugar content in the wort. Quite impressive, as many commercial craft breweries don't have these.

Leaving the brewery, we head off to pick up two of Stein's home brewer friends. These are Harald and Torbjørn Opshaug, both active home brewers with some decades of experience. As we're driving back to Stein's house, the three of them chatter away in Norwegian. From the way they talk it's obvious that they know each other very well. The comments and replies fly back and forth so quickly they sound more like a single hivemind than three separate people.

At Stein's house we go into the "kjellerstue," which is a kind of living room in the cellar. It's decorated with murals on the walls, wooden panelling, and old-fashioned wooden furniture of the kind Norwegians like to have at their summer houses. Hunting gear, beer bowls, animal pelts, and various memorabilia make up the rest. Here we're joined by Johan, who is a couple of decades younger than the oldest, executive in some big company, and also an avid home brewer. We sit down, and our hosts hand out the beer bowls.

My beer bowl |

Wooden beer bowls are an old tradition in Norway, with various forms in different places. Here they are straightforward bowls, painted, with a text around the rim. There's a long tradition for these texts going back several centuries. They are always short rhyming pieces, with the bowl itself speaking in the first person. The one I'm given has the text "I stood in green groves / now I slake thirsty mouths" (it rhymes in Norwegian). They tell us that these bowls are what they normally drink beer from.

It's at this point that we're supposed to get down to business. Now we can taste the beer, ask them how they brew it, and get a real clear picture of brewing in the region. Alas, it's not to be. Although these guys are in their late 60s or early 70s, they're clearly still fond of their drink, and generous hosts. The evening rapidly turns into quite a party, and although I do get lots and lots of information, structured questioning and note-taking is impossible. What notes I have were scribbled down rapidly the next morning, while packing with a hangover, before our 8-hour drive. So I'm left with a rather fragmentary picture. Unfortunately.

We start with one of Stein's beers. It's hazy, with a coarse white head, and obviously low carbonation. The taste is sweetish, with low bitterness, and the aroma is dominated by a strong fruity aroma, vaguely citric. I'm immediately reminded of the orangey flavour from the kveik in Voss, and look at Martin excitedly, saying "It could be. It doesn't have to be, but it could be." I tell Stein that "this fruitiness can't be from the hops, because of the low bitterness, so ..." The immediate laughing reply, from Harald, is "are you sure about that?" Then I remember. At the brewery, Stein told us he would often dry-hop the beer. So it's not the kveik, and in fact it turns out they didn't use any. It's an excellent beer, but not that traditional any more.

Left to right: Harald Opshaug, Torbjørn Opshaug, Francis Simard, Johan ??? |

During the course of the evening I gradually piece together a picture of what's been going on. They all started brewing traditionally. Originally, they would use local malts, pharmacy hops, and kveik, and they would make raw ale. That is, the kind of ale where the wort is never boiled. As they tell us, raw ale is a very different type of beer. They can tell immediately from the flavour if it's a raw ale.

Then, in 1990, Dagfinn Hovden, a home brewer from Ørsta (where my father is from) started an annual series of home brewer seminars. At this point, modern homebrewing is totally unknown in Norway. Indeed, it's only just starting to get going in the US (Papazian published his first book in 1984). These seminars were both a tasting competition of the type familiar to modern home brewers, except there was no division into styles, and a forum for exchanging tips and techniques. They studied Odd Nordland's book, recipes from old texts, and any other sources of technical information they could get their hands on.

Gradually, they started modernizing their beer. Harald tells us that when he made raw ale, now and then it would turn sour, unsurprisingly. After he started boiling it he never once made sour beer. They also gradually moved away from using kveik, because you have to be certain that the kveik is good before you use it. If it's not you get bad beer, and then a lot of work goes down the drain. Modern lab yeast is a lot less effort, and more reliable.

Troll family. The one with writing is winner's prize from the home brewer seminar. |

Thinking of the people in Voss saying the kveik is 350 years old, I ask Harald how old his kveik is. "Oh, that's easy. It's 20 years old." Nonplussed, I ask him what happened 20 years ago. "I got it from a guy up the valley." We discuss a bit, then agree that that doesn't really mean the kveik is 20 years old in any reasonable sense. Harald calls his kveik "godsorten" (a kind of pet name, literally, "the good sort"). When pressed he admits he's never made sour beer with it, but from how he speaks about it he seems to feel a bit uneasy about using it.

Martin tells me "I can tell from this beer that they're using American hops to recreate some of the kveik flavour they lose when using lab yeast." That's an intriguing notion, so I turn around and ask Harald if it's true. "No, no, no," he says immediately, then goes hesitant and starts squirming. "No, I don't think so... Well, perhaps. Or... I don't know." Maybe they do, maybe they don't. Clearly the brewers themselves never thought about it in those terms.

They ferment colder than in Voss. Exactly at what temperature I can't say, but they don't seem to have gone over 33C. They boil the juniper, then mash at 65C. When they boil, they reduce the wort by about 15% (but this is a recent innovation). Their wort is usually at 15-17 Brix. They also used to do their own malting, but gave it up, because of difficulties getting suitable barley, and because it's a lot of work.

They used to make "spissøl," that is, small beer from the second runnings. Typically they would add a lot of sugar to this. "So, you know, the spissøl would often be stronger than the main beer," says Harald, laughing. Traditionally, this was the beer for the farm hands.

Talking to them, these guys really impress me. I can ask them any question I want about how they brew, without any fear that they will be offended. They're clearly self-confident enough to have no issues in that regard. They'll listen to my question, consider it carefully, then say "yeah, well, we did like this. It might not be right, but it's what we did." The openness and willingness to learn from anyone who has something to offer is deeply impressive.

From the taste of the beers and what they tell us it's clear that their brewing now is much more modern than it was 25 years ago. Stein has stopped using juniper, but Harald still uses it. They don't seem to use kveik any more. The malts and hops are now imported, and so on. They've also modified the traditional processes based on modern knowledge of biochemistry, so the mashing now seems to be different, for example. As Harald says, much of the traditional, labourious processes are not necessary, since you can approximate the results easily in other ways. Using caramel malts instead of boiling for hours, for example.

They see this as progress. They are very much aware of the long tradition behind them, and in some ways proud of it. But, they say, the beer at the seminars 20-25 years ago was very variable. Much of it wasn't very good. That's totally changed now, they say, and obviously the transition to more modern methods is part of that. I can see why they consider it progress, but in some ways it's also a major loss to world beer culture. Because although they feel their beer is getting better (and maybe it is), at the same time it's becoming more like the beers made everywhere else. If it's improvement, it's improvement at the expense of diversity. Of course, if they want to brew the beer they like I'm hardly in a position to complain.

Torbjørn serving more homebrew (yes, the Coke bottle contains beer) |

Unlike these four, quite a few of the brewers in the region seem very closely wedded to the old ways. For example, there are still people making raw ale. Some use a lot of sugar, and ferment with bread yeast. Stein and his friends don't think these beers are very good. In Norddalen and Eiddalen (near Stranda) the brewers insist on making smoked beer, so after they've bought the malts from Stein they smoke it themselves. And in Hornindal they still brew with kveik, but it's gone sour. Apparently people there insist it should be that way.

Since we don't get to taste the beers ourselves it's difficult to know what to make of this. Are the beers really that bad? These guys brew very good beer, and they grew up in the tradition themselves, so they obviously know what they are talking about. On the other hand, none of the traditional beer we've had has been bad, and we know people sometimes have to acquire a taste for foreign flavours. Could Hornindal be Norway's "lambic valley"? Or do the 5-10 brewers there actually produce horrible, horrible stuff? Frustratingly, there seems to be no way to tell. But one thing is obvious: we could have spent more than a week just exploring Sunnmøre.

At this point Stein is really warming up, and keeps bringing out various curiousities. A pistol from the war. A dinner plate with SS markings on it. He even tortures me and Martin with a machine that goes bang in your face, then tickles you and shoots burning powder into your nose, to hysterical laughter from all present. The party is getting very lively indeed by now.

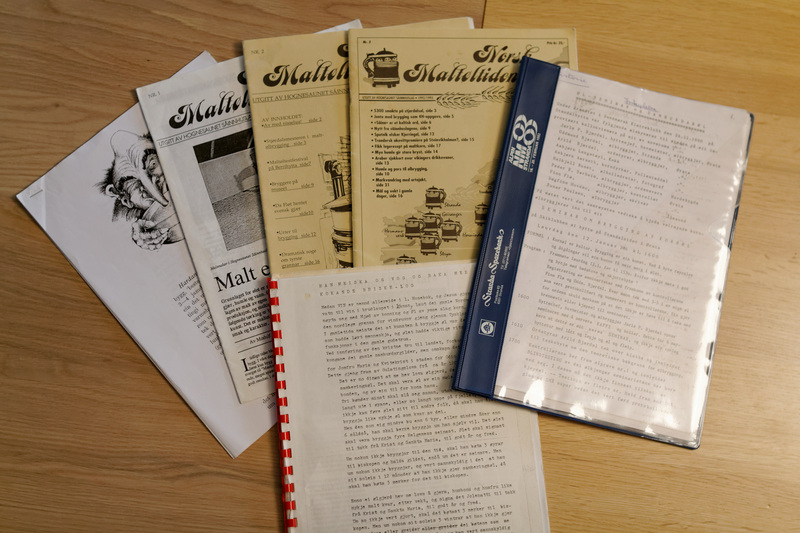

The documents |

Then Stein brings out a cache of old papers, which he shows to me. Three editions of a magazine for farmhouse brewers, from the early 90s. Written summaries of the first few brewing seminars in Sunnmøre, also early 90s. Old farmhouse ale recipes from Hardanger and Gudbrandsdal. A booklet on farmhouse brewing from Ørsta. It's a real treasure-trove of information, and seeing my interest Stein kindly lets me borrow it. I've scanned it and mailed it back to him. Analysis of this material is going to be very useful indeed.

Eventually, it gets late, and however much fun we're having we realize we have to think about our long drive the next day. So, reluctantly, we get up and leave. Johan, who is going our way, comes with us to show us the way, as we stagger down the road. The next day I wake up with my head spinning from the beer and all the information I'm trying to digest. We pack, then start on the longest drive of the trip.

Mountain pass leading out of Sunnmøre, toward Trollstigen |

Similar posts

Kveik analysis report

One of my goals for the Norwegian farmhouse ale trip was to see if kveik (family yeast) still existed in Norway, and to get samples if possible

Read | 2014-09-26 08:11

A family tree for kveik

In 2016 I was contacted by Canadian researcher Richard Preiss

Read | 2017-10-06 10:02

Storli Gard: Norway's oldest beer?

Leaving Sunnmøre we drove for many hours along narrow mountain valleys

Read | 2014-08-17 16:59

Comments

David - 2021-07-13 12:13:31

So Harold doesn't use the yeast he contributed to white labs?

Lars Marius - 2021-07-13 21:22:34

@David: That's right. I asked him specifically and he said he doesn't dare brew with it, but he propagates it at intervals to keep it alive.

These guys have been told over and over again by modern brewers that using kveik is wrong, and so they've lost confidence in it. My reading is that Harald so loves this kveik that he's keeping it alive even if he doesn't brew with it any more.

Liam - 2022-10-09 21:21:58

Perhaps you should pass on the message that even in faraway South Africa we have access to and brew with Norwegian kveik yeast. In fact I have three varieties in my fridges as I type this...

I have made some excellent beers with it. One that springs to mind was a super fruity NE IPA.

Shane Johnson - 2023-04-03 21:51:13

Have you shared any of those documents you mentioned you scanned? (The three editions of a farmhouse brewer magazine, the summaries of the first few brewing seminars in Sunnmøre, the old farmhouse ale recipes from Hardanger and Gudbrandsdal, the booklet on farmhouse brewing from Ørsta) Is there a way I could read them? Thanks!

Lars Marius - 2023-05-04 20:38:23

@Shane: I have not shared these documents, unfortunately. I've tried to offer the creators that I could put them on the web for anyone to see, but they'd rather do that themselves, they said. Unfortunately, they haven't.

Ryan Hodin - 2025-06-07 19:51:44

It's strange reading this more than a decade later, with an active culture of Stein's kveik in my fridge and multiple batches with it either bottled or in progress, knowing how my friends adore the results I get out of his yeast.

I do hope he and Harald know how much the outside world appreciates their yeast - Out in the meadmaking community the stuff is much beloved. Certainly a favorite yeast of mine. I'm very glad they made an effort to keep it alive even if they decided not to use it anymore.