Writing Japanese

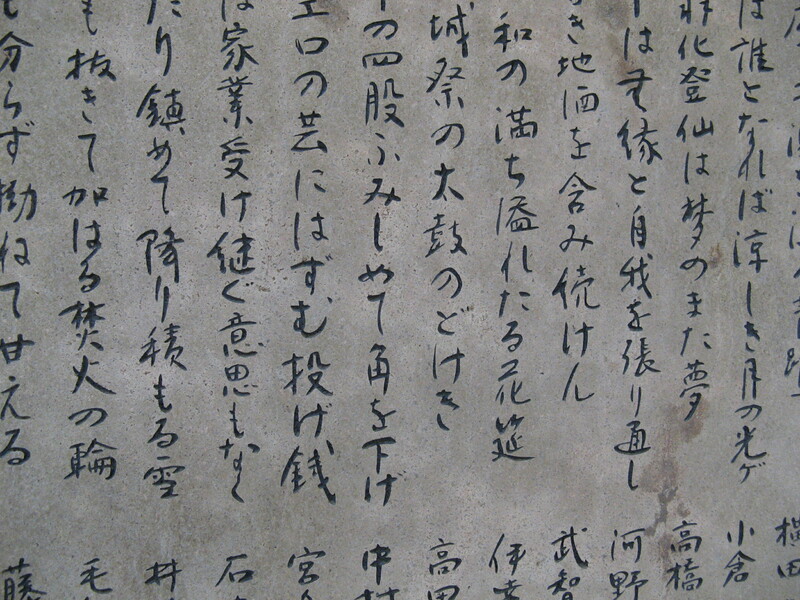

Inscription in stone, Dogo |

If speaking and understanding Japanese seems difficult, that's nothing compared to reading and writing it. The Japanese writing system is universally acknowledged to be the world's most complicated writing system, and with good reason. I'll try to give an idea of how it works here, without going too deep. (I don't know enough to take you too deep, anyway.)

Kanji

The basis of Japanese writing are the Chinese characters (called kanji in Japanese, and hanzi in Chinese), where each character represents one word. Thus, 日 is sun (or day) and 本 is book (or root). Together, as 日本, the two mean "sun's root" or Japan (or, if you will, "the land of the rising sun"). I called this script "Chinese characters," because Japan originally acquired it from China in the 4th century CE. Over the centuries, however, some differences have developed, so that not all kanji are exactly the same as their Chinese equivalents any more, and a few new characters have been invented on both sides.

Interestingly, the "communist" regime in China reformed Chinese spelling by simplifying the characters (reducing the number of strokes in many characters), while Taiwan and Japan continue to use the traditional characters. Thus, where Japan and Taiwan write 門 for gate, China writes 门. (If you have heard about Traditional vs Simplified Chinese, this is what it's all about.) Going to China and attempting to read Chinese there using a Japanese character dictionary after having picked up a handful of kanji in Japan first was a confusing experience, and it took me a while to sort this out mentally.

One thing people always want to know is how many Chinese characters there are. This is a tricky question to answer, because it's kind of like asking how many words there are in English. You can get by with knowing just the most common ones, and if you really dig deep you can find an astounding number. The same applies to Chinese characters. However, there is a standardized set of Japanese characters called the Joyo kanji, which is the 1945 characters people have to learn by the end of secondary school in Japan. So that gives you some idea. The full set used in Japan is said to be between 5000 and 10,000 characters, but if you include obscure and historical characters the true number will be much higher. Unicode 5.0 has 70,000 characters (many of which are not in common use), and there are Chinese dictionaries listing as many as 80,000. But knowing a mere 2000 should take you quite far.

Hiragana

Shinjuku (Tokyo) at night |

This system works fine for Chinese, where words are not inflected, but less well for Japanese, where they are. In other words: in Japanese there are many forms of the word "to eat" (as I wrote in the previous blog entry), but in Chinese there is just one. Thus, it's perfectly fine in Chinese to write 食, meaning "eat", and be done with it. But in Japanese you need to change the word depending on whether you mean "eat", "eaten", "not eat", "not eaten" etc. And when the script has no relation to sound, but is based on a strict shape-to-word correspondence, there is no way to do that.

The Japanese solution to this problem was to invent a script called Hiragana that is based on a shape-to-sound correspondence, just like our Latin characters. However, instead of each shape standing for a single letter, each shape stands for a syllable. That is, 42 of the 48 characters represent a consonant followed by a vowel (so "ka" is か, "ku" く, "ke" け, and "ko" こ). The remaining 6 are one character for each of the 5 vowels and one for "n".

This may sound like an absurdly restrictive system, and for English it would be. Here you need to remember the discussion of phonetics in the previous blog entry. These characters correspond exactly to the legal sound combinations in Japanese, which means that if you can't write a word with these characters it's not a proper Japanese word, anyway. The result is, of course, the mangling of loanwords I wrote about.

This provides a simple way to write particles like "ka", "wa", and "no", as well as verb endings and other grammatical inflections. It's also used to write some Japanese words for which there are no kanji, such as udon (a kind of noodle), shabu shabu (a kind of hotpot dish) and so on.

Katakana

Buddhas, Takahama |

However, it doesn't end here, because in addition to Hiragana the Japanese also use a script called Katakana. (Together the two are known as "kana".) It has exactly the same number of characters for exactly the same sounds, but the shapes are different. In fact, Hiragana generally has curvy shapes, while Katakana generally has straight, angular shapes. This means that with a little practice you can tell the two apart, even if you can't read them. In any case, the result is that you have to learn another 48 characters in order to be able to read Japanese.

Katakana is generally used for foreign loanwords, and there are a surprising number of loanwords from English in Japansese, so this is a good place to start learning, because words written in Katakana are words you are likely to know already. Beer, for example, is ビール, that is bi-longprecedingvowel-ru, and steak is スツーキ, that is su-te-long-ki. If you can read katakana (and guess what mangled English word is meant) you can pick up a fair bit, especially in Japanese-only menus.

This blog entry is already quite long, so I've skipped over a number of interesting digressions and in fact also some of the worst complexity of the system. Still, I think this gives a reasonable picture of how Japanese is written. I may fill in the remaining bits one day, if inspiration strikes, or people ask.

Similar posts

A new book on Topic Maps

Those of you who have been waiting for a new Topic Maps book will be happy to hear that one has just been published

Read | 2007-01-01 20:15

A trip to Beijing

This week I am in Beijing to teach Topic Maps to the developers of a Chinese start-up company, which is developing a new product based on Topic Maps

Read | 2006-05-23 18:06

Speaking Japanese

Like most other things Japanese, the Japanese language is in a class of its own

Read | 2007-07-25 20:39

Comments

Tore Hoel - 2007-08-01 03:37:54

Thanks, Lars Marius, for this enlightenment. I'm still jetlagged from two weeks in Niigata, Sendai, Mashiko and Tokyo. My menu was mostly beer, sake and the good food, ordered by pointing. With all the other impressions my mental capacity was stretched beyond any hope to pick up 1945 x 48 x 48... combinations of signs. May be the next time...

Lars Marius - 2007-08-01 03:41:38

Thank you, Tore. I must admit I haven't gotten very far myself, either. I can decipher some things, on menus and elsewhere, and with a character dictionary I can look some things up. Mostly it remains a closed book for me too, though.

Sonia P - 2007-09-26 11:45:28

Japanese looked so hard, but after moving to China I realized how hard Chinese language is...however, Japanese still seems like a lot to learn. I don't know why but Japanese language always seemed much more interesting. Anyways, Thanks for posting this.

Jonathan Rockway - 2007-09-26 18:10:42

> steak is スツーキ

Slight misspelling, it's actually ステーキ.

kentaro - 2008-02-22 14:22:23

I am a japanese. most japanese people only know about 2000-3000 kanji characters. we also use japanese simplified characters, that are usually simplified differently than those used in China, but are not the same as the kyujitai characters pre-ww2. even the most advanced kanji tests given by the government 日本漢字能力検定試験 which cover the old and new forms as well as very rare characters only cover 6000 characters, hardly any japanese know these characters. I don't think you would find a single living person in japan that would know 10000 characters or know how to apply them. An educated Chinese will usually know many more kanji characters than a japanese, though some of them may be different or not used at all in japanese.

my two cents, thank you!

Mike S - 2008-06-05 13:16:50

You're forgetting one other script in the Japanese writing system: 'romaji', or japanese expressed using the roman alphabet.

To complicate things further, there are predominantly two romanization schemes being used in Japan today. So the Japanese flute, for example, can be written in two ways:

shakuhachi - Hepburn system

syakuhati - Kunrei-shiki system

Lars Marius - 2008-06-06 04:58:25

Mike, I decided to skip romaji, since I felt this blog entry was long and complicated enough as it was, but you are of course correct.

Shadab Raza - 2008-07-09 02:22:08

How to write Thank you all in Japnees Script?

Lars Marius - 2008-07-09 04:53:00

Thank you can be said many different ways in Japanese, but a common way to put it is "arigato". That would be ありがとぅ. This is hiragana, literally a-ri-ga-to-u.

Charles - 2008-11-14 13:51:45

Itis a mistake to believe that the Japanees still use traditional kanji. For example 澤 (sawa) is now written 沢 unless in someone's name. Unlike in Taiwan, Kanji have been greatly simplified in Japan. They have not been simplified, however, to the extent of what has taken place in China.