The true meaning of Christmas

Brewhouse in the snow. Ulvik, Hardanger, western Norway. |

People often lament that we need to pay more attention to the true meaning of Christmas, but I don't think they mean the same thing as me when they say that. In English there are two words for Christmas. The first is the obvious one, meaning "the mass of Christ", the celebration of the birth of Christ. The second word, yule, derives from the original pagan feast which the church later co-opted, turning it into Christmas. Since it's the original one, of course that is the real feast.

In Scandinavia Christmas is still called "jul", recognizably the same word, and Scandinavian farmers hung on to the pagan aspects of the feast until quite recently. Of course, a thin Christian veneer was added on top, but most people seem not to have associated Christmas with Christianity at all until modern times.

So what was the original celebration? What do we know about that?

The oldest reference to the old pagan yule feast is a 9th century poem, which says of king Harald Fairhair that, if he got to choose, he would prefer to "drink yule" at sea. Back then, people seem to have said not "celebrate Christmas", but "drink yule". Beer was central to the feast in Viking times (as I've written about earlier), and it remains so today for most farmhouse brewers.

Oskoreia was a wild procession of dead spirits thought to ride through the air before Christmas. Here a humourous interpretation by Nils Bergslien, 1922. |

Back then, somewhat like now, the period before Christmas was much taken up with preparations like brewing, baking, butchering, and so on. A major difference is that people say the period before yule was often one of fear, because this was the time of year when all supernatural forces were known to be at their strongest. So much so that there were wild stories of people being chased out of their own houses by trolls on Christmas Eve. The trolls would then devour the Christmas feast. [3]

Here's a classic example:

On the farm Kvam in Aurland every year the trolls used to chase the people out of the house on Christmas Eve and take the yule feast for themselves. Then one year a stranger with a gun came to the farm on Christmas Eve, asking if he could stay the night. The wife on the farm said that they would be happy to have him, but they were so badly plagued by the trolls that they couldn't even stay in the house themselves. "There might be a cure for that," said the man.

When evening came and the feast was set out, the man loaded his rifle with a silver button, and hid on a large shelf along the wall. And, sure enough, before long a large group filed into the house, led by a huge troll named Trond. Trond took the high seat, and when he sat down his nose was so long it nearly touched the table.

One of the trolls went down in the cellar, coming back with a filled ølkjenge (beer bowl). Once up in the hall he lifted the bowl and drank, saying "this I give to you, Trond!"

In the same moment the man hidden on the shelf said "this I give to you, Trond!" and fired at the troll chief, who toppled over. The trolls broke up in confusion and fled, screaming as they left "yule in Kvam was short this year!"

It's a strange story: the people being chased out of their own home by trolls year after year, and specifically on Christmas Eve? Variants of this story were told in many places, and in many different forms and shapes. That's because the story is an echo of something deeper.

Jarand and Reidar Eitrheim preparing juniper infusion for the Christmas beer. Aga, Hardanger, western Norway. |

Quite a few places in Norway the tradition on Christmas Eve was to have a feast with good beer and food (just like today), and to, once the feast was over, put on new candles, add fuel to the fire, and then withdraw, leaving everything on the table. Many places people bedded down in straw, leaving their beds empty. [3] [4]

Clearly the stories are distorted memories of this custom, which must have been the original one. The trolls have been added to explain why people left the food and drink out, and seemingly abandoned the house, and the stories have been embellished from there.

But why was this the custom?

According to some ethnographers yule was a two-part feast, and this was only the first part. The first part is thought to have been a feast for the dead, very likely the ancestors. The food and drink was left on the table so that the ancestors could enjoy the delights of life again, and even sleep in their own beds for one night. [3] [4]

So, yes, part of the Christmas celebration was ancestor worship. In older times ancestor worship was very important, but that's too big a subject to drag in here.

The Slinde birch, where beer was sacrificed to the ancestors every Christmas until it blew down in a storm in 1874. Painting by I. C. Dahl, 1838. |

They also claim the second part was a celebration of the sun's turning and the beginning of the new year. This is logical, given the timing, and there is plenty of folklore showing that people firmly believed the end of the year, the turning of the sun, was a deeply significant moment. There were many, many superstitions connected with this moment, one of them being that one must not have beer fermenting when the sun turned, or it would inevitably go bad.

Feasting at the beginning of the year was important because people believed that as the year began, so it would continue. The idea was that if you ate and drank heartily at the beginning of the year you could deliberately set a precedent for the rest of the year. There were many such superstitions about using omens in this period to forecast the coming year because of the same belief. For example, if, the morning after Christmas Eve, whole grains were found under the table, harvest the next year would be rich. It was better if they were barley than oats. [3]

So if the ethnographers are right Christmas was first a feast for the dead, then a fertility feast for the new year. Both, of course, requiring the best the house could produce of food and drink. And in Scandinavia the best drink was beer, of course. But how much is this to be trusted? Can ethnographers really have reconstructed the original meaning of Christmas from fragmentary stories and traditions around Norway?

These things always seem very speculative, even if this theory makes sense, and matches what I've seen myself of the traditions. But there's a stronger reason to believe it's accurate.

Traditional Chuvashian house. Kshaushi, Chuvashia, Russia. |

Russian ethnographers, working from Russian material came to the same conclusion about the pagan midwinter celebration in Russia, except they switched the order of the two parts. Apparently this conclusion was formed by one prominent ethnographer, and then accepted as plausible, if not necessarily proven. [2]

I thought that in itself was very promising. Then I found this story, from Kharkiv province in Ukraine:

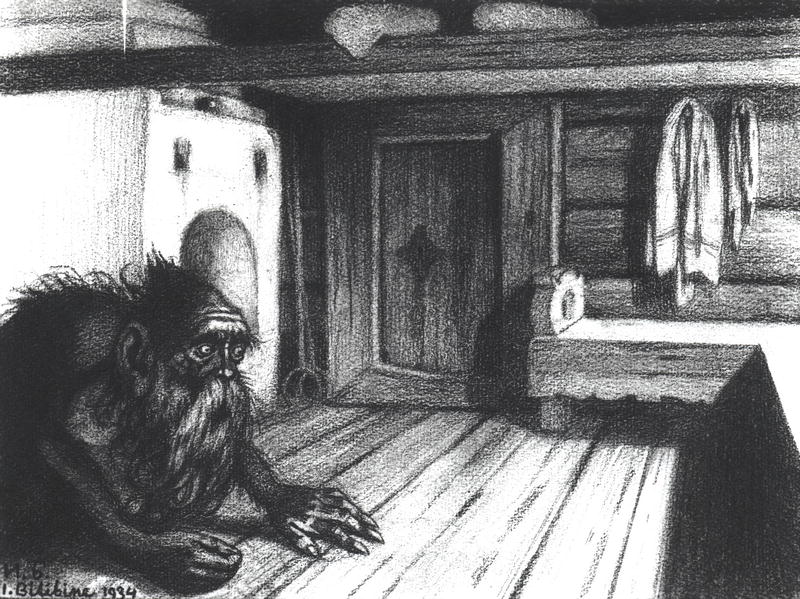

One Christmas Eve after a dinner with a fair amount of drinking, the household went to bed without clearing anything from the table. About midnight there was an uproar in the living room, singing, whistling, the sound of furniture, dishes breaking. The whole family woke up, but didn't dare investigate. They saw the domovoi sitting on the table breaking spoons and smashing plates. On the floor were overturned chairs and broken goblets. Finally, the master of the house made the sign of the cross, rose, and sprinkled the table with holy water. The domovoi disappeared. [2]

What the story means is that the exact same custom of leaving the Christmas feast out for the ancestors must have been practiced in Russia. Drinking was of course part of the Christmas dinner, and it's emphasized here to explain why the feast was left on the table. The domovoi was the supernatural guardian spirit of the house, and the disturbance is not entirely out of character, since in more modern times the domovoi took on a more capricious and prankstery character. What really clinches it, however, is that every authority agrees the domovoi originally was believed to be the spirit of the household's ancestors.

Domovoi. Drawing by Ivan Bilibin, 1934. Wikimedia Commons. |

So it really does seem that the real, original meaning of Christmas was to eat well and drink a lot of beer, both for yourself, for the promise of the new year, and as an offering for your ancestors. In fact, in Old Norse the word yule was generally used as a synonym for a feast, so the feasting definitely is central to the whole concept.

But why would the Scandinavians and the Russians have the same original pagan Christmas customs? For the same reason that we speak related languages, believed in basically the same pagan pantheon, and shared a belief in the personified ancestor spirit the Russians call domovoi and we Scandinavians call nisse: we all descend from the same people, the Proto-Indo-Europeans.

Two 'nisse' playing cards. Note the ølkjenge. Drawing by Nils Bergslien (from Voss), 1887. Nationalbiblioteket. |

If the origins of the Christmas feast really lies that far back, and I don't see why it cannot, it goes very far back indeed. According to Anthony 2007 [4] the Slavic and Germanic peoples parted ways in about 2500 BCE, 4500 years ago. That's just after the Egyptian Old Kingdom was founded, about 150 years after the death of the first pharaoh. Or 1800 years before the traditional date for the founding of Rome. Or, if you will, 2500 years before the birth of a certain baby boy in a crib in a stable.

In short, this Christmas you can eat well and drink strong beer in good company, in the certain knowledge that you are participating in the real, true meaning of Christmas.

Sources

[1] The Horse, The Wheel, and Language, David W. Anthony, Princeton University Press, 2007.

[2] Russian Folk Belief, Linda J. Ivanits, Routledge, 1989.

[3] Vår gamle bondekultur, Kristoffer Visted & Hilmar Stigum, Cappelen, 1952.

[4] Jul i Norge : gamle og nye tradisjoner, Ørnulf Hodne, Cappelen, 1996.

Similar posts

When not brewing Christmas beer was illegal

There really was a time when not brewing Christmas beer in Norway was not just illegal, but even punished harshly

Read | 2019-12-07 17:02

The yeast scream

A strange custom they have in Stjørdalen in Norway is to scream into the fermenter as they pitch the yeast

Read | 2017-01-25 16:58

Gildet på Solhaug

A week ago or so I received an email from my girlfriend about a play she wanted to see at the National Theatre: Gildet på Solhaug, or The Feast at Solhaug, by Ibsen

Read | 2006-04-02 21:10

Comments

na - 2020-12-16 14:01:45

There were also a lot of contact between slavic and norse people in old times, so one can speculate that they might share some cultural superstitions like that. Some even say that the name Russia has roots in swedish vikings rowing down east european rivers. Thor Heyerdahl had his "Jakten på Odin" theories as well, though I don't know if these are reliable.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2020-12-16 14:06:31

@na: Yes, that's true. There certainly were a surprising number of cultural similarities between the Russians and the Scandinavians. And it is possible that the customs just spread, although there's no obvious reason why one group would adopt the midwinter celebration customs of another.

If you look at Finnish midwinter celebrations, as described in "Finnish Folk Culture" by Ilmar Talve, for example, they look different. And the Finns are not Indo-Europeans, but they were ruled by the Swedes for 700 years.

There are also some surprising similarities in the Iranian midwinter celebrations (see commented-out paragraph near end in HTML source of blog post). And the Iranians are Indo-Europeans.

But I agree both explanations are possible.

Ignas - 2020-12-17 09:34:12

I'm Lithuanian and during Christmas Eve we followed a few of old pagan traditions passed on from older generation. It would depend on the family but most would leave the food on the table uncleared (on purpose :) ). If a person had died recently there would be a fresh set of plates and cutlery for them during the feast. Similar to American tradition of milk and cookies for Santa. Families that were more serious about old traditions had many games guessing what the next year would bring, e.g. how prosperous will it be, will you get married and have children. I remember finding it tedious at the time but now it's nostalgic and happy memories :)

Lars Marius Garshol - 2020-12-17 10:35:25

@Ignas: Wow. That's really interesting. Definitely the exact same custom. Thank you!

Rhonda - 2020-12-18 15:04:36

I absolutely love this, Lars - what a treat and a fascinating read!

Mika Laitinen - 2020-12-21 17:14:44

Fascinating reasoning! In the past Finnish farmers ended their farming year with a harvest celebration called Kekri. This celebration marked the end of harvest and the beginning of a new farming year. It was celebrated with food, ale, and leisure time. The feasting included rites to secure good crops and luck with farm animals in the forthcoming year.

This feast was between late September and early November. The timing was not precise and it used to vary from house to house and region to region. It seems that many of the Finnish Christmas traditions have been shifted from Kekri to Christmas. Kekri is still a known feast but it has largely lost its meaning and importance.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2020-12-21 21:42:06

@Mika: The reasoning behind kekri seems to have been different: that it was about reconciling the lunar and solar years, so that you got this "leftover period", which was when the festival was celebrated. Talve says early November.

There are some similarities, in that it, too, was a time for remembering the dead + new year, but it seems different in form.

I think it's also significant that the Finnish words for Christmas are lendwords: joulu and juhla. As far as I can tell the Finnish Christmas is an import and kekri is probably the original new year feast.

(Thanks, btw! :-)

Christian - 2020-12-22 13:24:25

Hi, it is nice writing about old customs, just to make things clear - christian Christmas did not originate or were not co-opted from pagan feasts, it simply would be no logical and against Christian faith, more on topic https://judicialsupport.wordpress.com/2017/12/15/the-myth-of-the-pagan-origins-of-christmas/

Lars Marius Garshol - 2020-12-22 16:06:36

@Christian: In the case of Scandinavia the sources are clear that the yule feast was moved from its original dates to December 25, to conform with the Christian feast by then already being celebrated on the continent.

But there is absolutely no doubt whatsoever that the pagan feast was co-opted by the church and turned into a celebration of the birth of Christ. The page you link is basically deceptive. Most of their arguments are correct, but also misleading, and from the text it seems quite clear that they are aware of it.

Christian - 2020-12-23 21:14:40

@Lars thanks for your reply. When it comes to what you say: "But there is absolutely no doubt whatsoever that the pagan feast was co-opted by the church and turned into a celebration of the birth of Christ."

I know this myth is very alive and everybody heard somebody claiming that, but do you really have some reliable sources backing "co-opting by the church" theory, rather than new and old traditions naturally mixing and merging?

That is another interesting discussion by deeply educated persons on topic https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=FcpSo2pRhWA&feature=youtu.be

Lars Marius Garshol - 2020-12-23 21:42:10

@Christian: In the case of Norway, Snorri Sturluson records that King Hakon the good moved the old yule feast to align it with christmas, and that he added provisions forcing people to bless the beer in the name of Christ and the virgin Mary instead of the old gods. So that's one example of deliberate co-opting. (You could argue this was the king rather than the church, which is fair. There was no organized church in Norway at that time, and christianization was driven by the kings.)

In the case of Britain we have the later pope Gregory I's own letters saying that it should be church policy to convert pagan festivals into Christian ones: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christianity_and_paganism#The_Anglo-Saxon_conversion

This practice applied to temple locations and other traditions, too, and is sufficiently well known to have a name: Interpretatio Christiana. That this was common practice is widely recorded in the writings of early important figures of the church, so the issue is well beyond serious dispute.