Did People Once Drink Beer Every Day?

Carrying water. Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo. |

Martyn Cornell has been fulminating against what he calls The Great Medieval Water Myth: that the peasants drank ale all the time because ale was safe to drink while water was not. He concludes that it's wrong, and that English peasants mostly drank water.

However, I think the real picture is a lot more complicated.

I've been collecting data on this for many years with a view to eventually settling this issue definitively. That job isn't complete yet, but there's such a backlash setting in against the "myth" that people seem to be giving the wrong impression in their enthusiasm, and I feel the need to clarify a little.

Let's start by breaking the "myth" down into its individual claims, so that we can judge each one. The claim is that in the past

- Water wasn't safe to drink,

- and people knew it, so they avoided water,

- and instead had beer as their everyday drink.

Let's go through these one by one.

Well. Kshaushi, Chuvashian Republic, Russia. |

Water wasn't safe to drink

This ought to be uncontroversial. It's not that water always made you sick, but the risk was always there.

Cholera, generally spread through contaminated drinking water, used to be a major killer. The 19th century alone saw six global cholera pandemics, each of which killed millions of people. And cholera was and is definitely an issue in rural settings, not just in the cities.

The parasite Giardia lamblia can easily be caught from water even in remote unpopulated areas. In fact, the disease it causes is known as "beaver fever", because you can get it from water from beaver dams. Even modern waterworks are not entirely safe against this parasite, as the 2014 outbreak in Bergen, western Norway, shows.

E. coli is a common cause of diarrhea. This bacteria is quite common in private wells. Indeed, Sigurd Johan Saure, owner of kveik #8, told me that the well on his farm had been tested, and E. coli-like bacteria were found in it.

The list of common waterborne diseases just goes on and on and on, and in a huge number of them a common factor aiding their spread is lack of proper toilets for humans, lack of control over animal faeces, and effluent from both seeping into human drinking water.

The normal setup for Norwegian farms was to have the farm high up, so that these effluents would run down into the surrounding fields, effectively fertilizing them[2, p53]. Animal manure was carted out manually for the most part, but natural runoff also helped, by design. And the well would usually be at lower nearby elevations, for obvious reasons.

Standard Swedish peasant toilet. Yes, that wooden bar is the seat. The ground is the ... ah ... receptacle. Bunge county museum, Gotland, Sweden. |

I really should not have to be telling you this. The UN and many charitable organizations have been running huge campaigns to bring clean drinking water to people around the world for decades, and there is most definitely very serious reasons for that.

Here in Norway the Food Safety Authority has the responsibility for overseeing the quality of water from waterworks, which they do by approving plans, testing the water, etc. Again, there are very good reasons why all of these safeguards are in place. Norway does not spend lots of time and money on water quality every year simply because it amuses us. And even so it sometimes fails, as the giardia case above shows.

So while you could often get away with drinking water, there was always a not inconsiderable element of risk to it.

Water spout, Shiogama, Japan. |

People knew water wasn't safe

On this part I have very little evidence. Astrid Riddervold wrote that there was a 1939 survey in Norway where people were asked about drinking water, and that they overwhelmingly replied "we did not drink water, we were afraid of the water."[3] That sounds super useful, but unfortunately, I have never been able to figure out which survey this was, and so I cannot say much more about it. (Maybe it's massive evidence, or maybe it doesn't tell us anything. Context and detail will decide, but we don't have them.)

In general it does seem that people did drink water, but it's not clear how often. For work the peasants would typically bring non-water drink with them. But people travelling or hunting or doing other work far from the farm must often have resorted to drinking water. Quite possibly they drank water at home, too.

However, what is strikingly clear is that people put a lot of effort into having things other than water to drink. There were a whole host of different drinks that people made, and they all feature either heating, fermentation, or souring, which means they will have been safer than water.

People made juniper berry beer, kvass (from flour or kitchen leftovers or sometimes both), fermented birch sap, a drink from the soured mash, and a range of sour milk-based drinks. Later they boiled various types of herbal teas from caraway, St. John's wort, and so on. (Chapter 8 in [4] goes through this in much more detail.)

Water basin, Tsumago, Japan. |

So people put a lot of effort into having something other than water to drink, but we don't really know why. Was it because there was nutrition in the other drinks? In a time when people struggled to get enough calories that was hugely important. Was it because they were safer than water? Or was it simply because people got tired of drinking water and they wanted something with flavour?

I lack hard evidence, but all of these are possible.

The great Swedish botanist Linnaeus writes in 1749 that water was man's original drink, and therefore the "noblest", "but water differs so much, and is of as many kinds as the soils, and also in many places distasteful and harmful. Therefore man has sought, through the boiling in water of herbs and seeds, to make it more tasteful and healthier."[1, p1]

That's pretty much the water myth right there: water was unhealthy, but turning it into beer made it less harmful. However, this is only Linnaeus, and it doesn't prove that everyone thought the same. It does show, however, that at least some people were aware that turning water into beer made it less harmful.

Martyn went deeper into this in 2014, and the short summary seems to be that people's views on water were mixed. Some thought it was unhealthy, but some also thought the opposite. My guess is that this is probably accurate.

Water lilies, Helsinki, Finland. |

People had beer as their everyday drink

The story of John Snow and the cholera-infected water pump in London is actually quite instructive. John Snow worked out that people in one part of London were coming down with cholera because they got water from a specific pump in Broad Street, and concluded the water was to blame.

There was one anomaly, though. None of the workers at the nearby Broad Street brewery got cholera. The reason was simple: they got free beer at the brewery, so they didn't drink water, and hence did not get sick.

This seems to be pretty close to the general rule: those who could drank beer for thirst, while those who couldn't had to make do with what they could get. In London that would be water, while farmers in the countryside had more options (sour, weird milk-based drinks, etc).

(Note that it's not true, as some people were saying, that only this single pump was affected. This outbreak was part of the worldwide 1846-1860 cholera pandemic, and removing the pump handle "hardly made a dent in the citywide cholera epidemic", as Wikipedia says.)

If we look at Norway, farmers there only had enough grain to brew once or twice a year, and so they couldn't drink beer every day. The most common drink was not water, however, but a milky drink known as blaand in English. In farmhouses the container of blaand had its customary place just inside the door, with a lid on it, and a ladle on top of the lid, for anyone to grab a drink any time they wanted. The blaand was supplemented with fermented birch sap, fermented juniper berries, and so on.

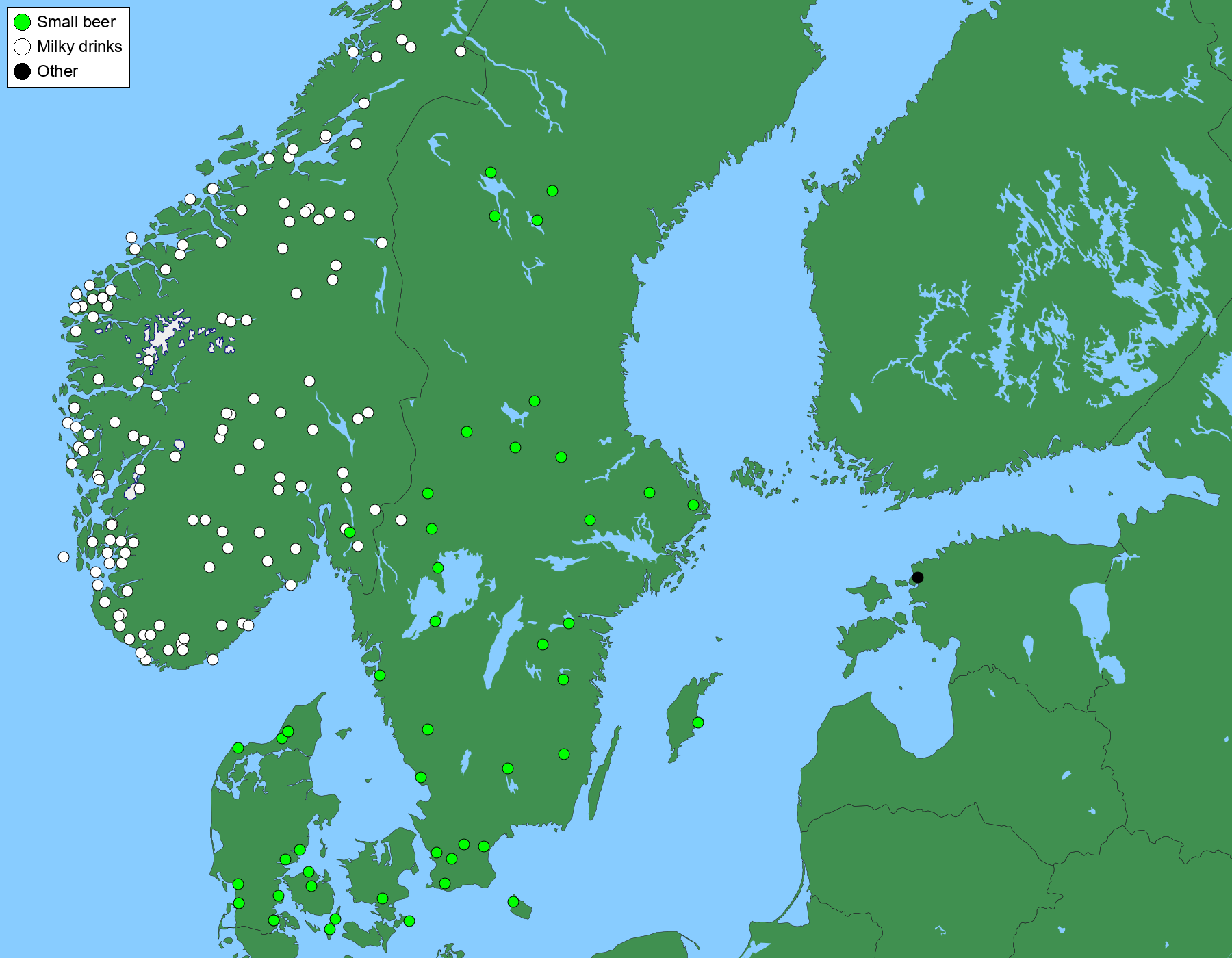

What did people have as their daily drink? |

Sweden and Denmark are further to the south, and a completely different story. In both countries the norm was to brew new beer every time the barrel was empty. Beer literally was the everyday drink against thirst to the point that in Denmark the most common name for the weaker beer was "dagligøl" (daily beer), while in Sweden beer was just known as "dricka" (drink) or "svagdricka" (weak drink).

It's difficult for people today to accept this as fact, but nevertheless people really did drink beer all day every day (where they could). Here's a quote from a Danish farmer describing his own upbringing: "People drank a lot of beer, and only beer. Nobody would think of drinking water or milk."[6]

A favourite quote of mine, from Sweden: "Juice was not on the table. Such things are not served for an ordinary meal. The soft drinks were not invented yet, and often there was not enough milk. Guess, then, what the five-year-old drank with the food." (This is a person answering a questionnaire on what he did in his own household. [5])

In Denmark it remained common to drink beer at work up until the last couple of decades. In the 1990s the luggage handling workers at Kastrup airport in Copenhagen went on strike when management proposed to end their free lunchtime allowance of beer. At Carlsberg workers went on strike when their 3 free beers during the working day were cut in 2010.

I could go on for a long time citing examples. The Danish king established his own brewery in Copenhagen because his navy was completely dependent on beer as the daily drink for sailors, and he was worried that in a crisis the navy might run out of beer and effectively be grounded.[10, p113] In Bergen, Norway those staying at the hospital founded in 1276 were to each receive 0.675 liters of beer every day.[9, p139] It just goes on and on.

Container of blaand with drinking ladle on top. By custom these were placed just inside the door for anyone wanting a drink. Photo from [2]. |

Of course, the full picture is even more complicated than this. I said Norwegian farmers didn't drink beer every day, but in Norway there will have been a few farmers rich enough to drink beer every day, and they very likely did. Just as in Sweden and Denmark there were people who were too poor to afford beer every day. Some people probably could not afford beer at all.

These claims are entirely consistent with the data Martyn quotes: England in the Middle Ages did not produce enough grain that every person could drink beer all the time. That will mean that a lot of people didn't drink beer all the time, which shouldn't surprise us, as many people starved to death from time to time in this period. However, those who could will no doubt have been drinking beer every day.

In later periods it was clearly very common to drink beer every day in England. Cobbett writes in that in the 1780s "to have a house and not to brew was a rare thing indeed"[7, p11], and he wants to restore this happy condition. To do that he explains how to brew, but starts out by calculating the cost, where he makes the assumption that "he uses in his family two quarts of this beer every day"[7, p16].

George Ewart Evans writes of Blaxhall in Sussex: "Beer was the usual drink in most households in this parish right up to the beginning of [the 20th] century." He goes on to say that people also drank tea, but it was expensive.[8, p60]

Foggy lake Måsvatnet, Romsdal, western Norway. |

Conclusion

I think it should be abundantly clear by now that in the past lots of people did in fact drink beer against thirst every day. This is not as simple as Martyn being wrong, however, because he's absolutely right that a lot of people couldn't afford to do it.

It's also not entirely clear why people drank beer every day. Probably because they liked it, and because it was healthy in the sense that they got enough nutrition and it didn't make them sick. Many people were also skeptical of water, but how many, when, and where is still not clear, and there certainly were people who were not skeptical of water.

Sources

The map of what people report as the daily drink in various areas is lacking a lot of data, and the reason is that I started on it last year. With 8000+ pages of archive documents and thousands of pages of published sources it's going to take years to complete it. Eventually it will be filled in and published properly.

[1] Beskrifning om Öl, Carl von Linné, reprint by Norstedts förlag, 1924. Original from 1749.

[2] Vår gamle bondekultur, volume 1, Kristoffer Visted, Cappelen, 1951.

[3] Norsk drikkekultur, Astrid Riddervold, Cappelen Damm, 2009.

[4] Historical Brewing Techniques, Lars Marius Garshol, Brewers Publications, 2020.

[5] Gotlandsdricka, Anders Salomonsson, Etnologiska sällskapet i Lund, 1979.

[6] NEU 2912, Skørping, Denmark, 1944. (An archive document held here.)

[7] Cottage Economy: Containing Information Relative to the Brewing of Beer, William Cobbett, C. Clement, 1821.

[8] Ask the fellows who cut the hay, George Ewart Evans, Faber & Faber, 1956.

[9] Or Noregs bondesoge : glytt og granskingar, volume 1, Sigvald Hasund, Noregs boklag, 1942.

[10] Beer and Brewing in Pre-industrial Denmark, Kristof Glamann, University Press of Southern Denmark, 2005.

Similar posts

Aarne Trei, a koduõlu veteran

From the previous stop we drove just a few kilometers, to meet brewmaster Aarne Trei

Read | 2018-02-18 11:45

Oppskåke

In older times there were a whole host of detailed social customs around the drinking of beer, but the only one I'm aware of that has survived into the present day is oppskåka

Read | 2016-02-14 12:45

Olga's beer

I had been googling "landøl" to see if it really was the name for Danish farmhouse ale, when I stumbled on a recipe for it

Read | 2020-08-09 14:38

Comments

Pedro - 2022-10-15 14:19:50

Interesting, thanks for link both of Martyn's articles as well.

I wonder if trying to figure out "why" is always the wrong question: as the other blogger I read (A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry*) people in the past might not care HOW something works, just that it did. In that sense, they didn't need to justify why they did what they did, only that they liked it/worked for them and didn't kill them.

* Readers here might like the series on ancient and medieval farming: https://acoup.blog/2020/07/24/collections-bread-how-did-they-make-it-part-i-farmers/

Dave Pawson - 2022-10-15 15:08:10

Muddy in detail, but fairly clear in overview Lars? Those who could did, with fair - good reason!

Lars Marius Garshol - 2022-10-15 15:29:45

@Pedro: I agree that establishing "why" may be difficult for questions like this one that are just as much cultural expectations and habits as conscious decisions. People may have ended up mostly drinking other things than water simply because that worked well and there were no strong forces pushing them away from it.

I'd still like to learn more and get deeper into the issue, though.

@Dave: Yeah, that's a good summary.

Martyn Cornell - 2022-10-16 14:47:03

I'm always delighted to be challenged by people who know what they are talking about, and I'm very happy to see this debate taken further.

A few quick points:

1) I think we have to draw a distinct line between the medieval period and the early modern period (circa 1500 and afterwards), when the drinking of ale/beer certainly looks to have been normalised, judging by the records we have; and there is definitely also a line to be drawn pre- and post-Black Death (1350). I think much of the evidence for the ubiquity of ale drinking is from the Early Modern period. In the Medieval period, and especially beforee 1350, I suggest, it was rather different. One important piece of evidence here is from Ælfric’s Colloquy, written by a Benedictine monk circa 1000, as a series of questions and answers designed to teach young people Latin, one passage of which goes

Ond hwæt drincst ∂u? (And what do you drink?) Ealu, gif ic hæbbe, o∂∂e wæter gif ic næbbe ealu (Ale, if I have it, or water if I have no ale)

which strongly suggests ale was not universal at that time.

The rise in ale/beer consumption, and the normalisation of ale/beer drinking, must have been down to the rise in arable agricultural productivity. Arable productivity looks to have fallen through the late medieval period, and then begun to roar away from the 16th century, thus providing the surplus to enable more ale/beer to be brewed.

2) People drank ale when they could because it's a more pleasant drink, not because the water was bad. The water I get out of the tap here in Cromer is entirely safe, but most of what I drink is tea, coffee, beer or juice, because I prefer them. See Ælfric above.

3) The Snow pump story works ONLY if most/all other pumps/sources of water in the vicinity are safe. The map Snow drew of outbreaks of cholera clearly centred on one pump. Indeed, there was one outlier in Hampstead where it was discovered that the householder actually sent for water from the Broad Street pump because she preferred the taste. To quote Snow himself:

"there has been no particular outbreak or prevalence of cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump well."

The conclusion has to be, then, that most water sources were safe. Indeed, "Asiatic cholera" was not seen in Europe until the early 19th century.

Let the arguments continue!

John Horn - 2022-10-18 20:22:46

Lars,

I appreciate your thoughts on this topic. I was in the middle of reading through chapter 8 in Historical Brewing Techniques when I heard about Martyn's post. Naturally, I was a little agitated.

I lay no claim to the having adequate knowledge to contribute much to this conversation. But having traveled extensively in developing countries, safe water is certainly a huge issue to date, and I don't see how things could have been better historically in England or Norway. I look forward to hearing more about what you find!

Roel mulder - 2022-10-20 09:04:27

Just a thought, but if water was unsafe... what did the animals at the farm drink??

Alexander - 2022-10-21 00:49:15

Just wanted to add that "beer" also needs a bit of definitions around it, there's all sorts from the strongest to the weakest, including watered-down beer. I seem to have a slot in my memory for hearing somewhere about the concept of quaffing beer, a low-alcohol watered-down daily drinking kind of beer, but I can't remember if this is in a Norwegian or a more metropolitan European context. But I'm sure it had a medieval context.

I think it has always been common knowledge that flowing water is better than still, going all the way back to ancient times, without people knowing specifically why that technically is. And I also think that when we talk about water being a "problem", it's most often a city / suburban problem, so that has to go into our historic context as well. Sure, we get cholera outbreaks in London in the 17th century, but that's not very related to the concept of what a medieval peasant drank, for example, in the Scottish highlands or at the banks of Glomma.

Love the blog, btw, love to see it still going!

Jeremy Hunter - 2022-11-19 21:01:52

If those repeating this myth base the argument on the fact beer is brewed, ie boiled, then if it's merely the boiling that was of interest to these people of the past, why go to the effort of making beer? They could just... boil the water. Unless there was more to it than that, such as nutritional value or that as you say, they just were bored of water.

Brent - 2023-08-30 15:55:50

Interestingly there are a few 1600s writings by William Bradshaw "of Plymouth Plantation" that elude to water being known as dangerous. Here is one quote: "The change of air, diet and drinking of water would infect their bodies with sore sicknesses and grievous diseases"