Danish farmhouse ale

Old Danish house, Svendborg, Denmark |

Danish farmhouse brewing appears to be almost entirely dead today, but it was once thriving all over Denmark, and it died fairly recently. Apart from one very brief summary hidden in a Danish dialect dictionary I don't know of any attempt at a comprehensive description of this brewing culture. So when I discovered that extensive ethnographic surveys of Danish farmhouse brewing existed in two places in Copenhagen I spent three days photographing 126 separate responses in order to get a picture of Danish farmhouse ale.

126 responses is actually a lot of data, so I haven't yet had time to go through all of them, but I've analyzed 21 in detail. The most startling thing is how similar they are. I found 3 different processes, where one dominates totally (17 responses), and another is only very slightly different (2 responses). This is in total contrast to the data from Norway, where everything differs wildly from response to response.

Survey responses (just a fraction), National Museum, Copenhagen |

Of course, this is easily explained. In Norway, people live in deep valleys between high mountain plateaus, or in between huge forests. Internal communications were quite difficult, and in places downright dangerous. Denmark, on the other hand, is flat as a board and very densely populated. One could easily walk from village to village. This is obviously going to produce a more homogenous beer culture.

Another clear difference is that in Denmark it was much more common to buy the malts and the hops. Again, the geography is a large part of the reason. A local maltery could serve a much larger population in Denmark, and thus be more profitable. Similarly, transporting hops around in Denmark was vastly easier than in Norway. One thing that stands out in the material is how many people would buy hops from itinerant hop merchants from Funen. These would drop by at roughly the same time every year, allowing people to stock up at a predictable time.

Everyone, however, appears to have had their own yeast, in exactly the same manner as Norwegian kveik. Many different methods were used for preserving the yeast: yeast rings (just like in Norway), drying on a brick, drying on a straw ring, or keeping it in a pot. Pitch temperatures appear to have been in the 25-37 C range. Unfortunately, all of these yeast strains now seem to have died.

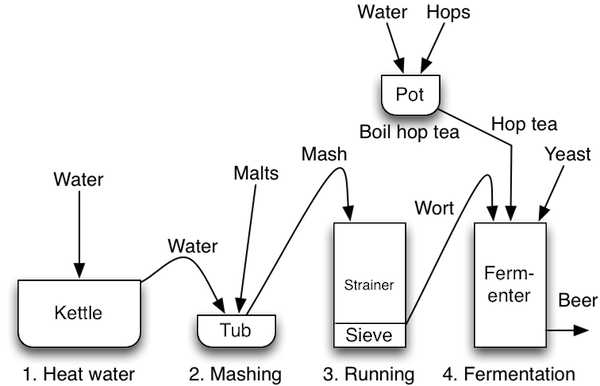

The Danish brewing process |

I've outlined the brewing process in the diagram above. Basically, it's the most straightforward raw ale process, where one starts with a simple infusion mash. Then, the mash is moved to the strainer, and run off directly into the fermenter. Hops are boiled in water on the side, to make hop tea, which is then added to the fermenter. Cool the wort, then pitch the yeast.

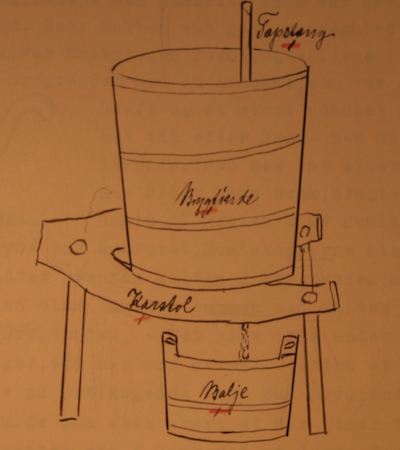

The Danish strainer, drawing by Jens C. Andersen, Gylling (from the collection at the University of Copenhagen) |

The term "strainer" needs some explanation. It's really a lautering tun, but farmhouse lautering tuns are different from the commercial ones, so I've chosen to adopt Odd Nordland's term for it. In Denmark it seems to near-invariably be shaped as in the drawing above. It's a deep wooden vessel, placed on a kind of stool. In the bottom of the vessel, off to one side, is a hole, closed by sticking a rod into it. Lifting the rod allows the wort to run off into the bucket below the stool. The filter in the strainer is straw in Denmark, usually tied in a ring around the rod, sometimes weighted down with stones. Usually there is more straw loosely piled on the bottom and the ring.

Even though this was raw ale many people write that in March/April people would brew a beer called "gammelt-øl" (literally "old beer"), which was stored until autumn. This was brewed the same way as the ordinary beer, but stronger, and with more hops. So this is a raw ale that was intended to be stored for six months. Clearly it is possible to brew raw ale that lasts at least that long.

In large parts of Norway people would brew only a few times a year, because they didn't have enough grain to brew more often. In Denmark this doesn't appear to have been a concern at all, so people would brew once a month, or every three weeks, or when the beer ran out. As far as I can tell, only barley was used. This is probably because people didn't have problems growing barley the way people did in Norway.

Woman brewing (press photo from Den Fynske Landsby) |

It seems that one of the uses for the beer was to serve it to servants, probably as part of their pay. One respondent writes that "it was said about some rather stingy people that they always had sour beer, because then their servants wouldn't drink so much."

One striking thing is the near-total absence of juniper. Juniper was used in nearly all farmhouse ales in Norway, and it was widely used in at least parts of Sweden. In Denmark the only place they mention juniper is Bornholm, which is so far east it's actually closer to Sweden than to Denmark proper. So probably that's due to influence from Sweden.

It's clear from the responses that in the 19th century people brewed all over Denmark, except the island of Anholt. The reason is probably that the soil on Anholt doesn't allow agriculture, so there was no grain to brew from. The respondent writes that people might brew for weddings, but if so they would buy the malts on the mainland.

Danish country house (by Koburg on Wikimedia Commons) |

So what happened to all this brewing? That's difficult to say. Most places it had died out already at the time the responses were written. Per Kølster found an old woman on northern Funen who was still brewing in 2005, so probably the tradition is not yet entirely dead, but that's the only sign I've ever seen of it still being alive anywhere.

One response, however, is quite striking. It's from Bredstrup, just outside of Fredericia on Jutland. The response is written in 1971, and the respondent writes that lots of people are brewing, even young people. The young people make it a point of honour to brew better beer than others. The local yeast was still alive, too. That's over forty years ago, however, so who knows what's happened since. I've tried contacting local home brewers to see if I can learn more.

There is a lot more information in the responses, but I think this is enough for one blog post. From what I've seen of the responses so far there is enough information to write a small book on Danish farmhouse ale. That will have to wait, though.

Below is a map of all the responses. Update: The red dots are for AFD (University of Copenhagen) responses, blue for NEU (National Museum), and the single black dot is the brewer Per Kølster visited.

Similar posts

Norwegian Ethnological Research

The definitive book on Norwegian farmhouse ale is Odd Nordland's "Brewing and beer traditions in Norway," published in 1969

Read | 2014-09-15 15:38

The juniper mystery

When I started looking at farmhouse ale back in 2010, one of the first things that struck me was that nearly everyone seemed to be using juniper

Read | 2017-02-02 09:43

Norway: climate and ingredients

Norway may not be the world's biggest country, but it has considerable geographic variation

Read | 2015-05-19 10:53

Comments

Matt - 2015-09-10 18:48:02

Was there any indication how long the hop tea was boiled for, or the amount of water to hops etc? I'm assuming there were not timed hop additions to the hop tea.

Lars Marius - 2015-09-11 02:24:28

@Matt: In general people haven't described the boiling of the hop tea very much, but the impression I get is that they would use 2-3 liters of water, and boil for about an hour. I'd need to analyze this more carefully to say anything more. Note that batch sizes seem to typically have been around 150 liters.

Chris - 2016-01-22 08:17:46

It's a shame that you haven't found the same kind of active farmhouse brewing as you did in Norway. Based on your research, have you tried to recreate any Danish beer?

Lars Marius - 2016-01-22 08:23:16

@Chris: I've found a few indications that it might still be alive in northern Funen, but I haven't followed those up yet. I've yet to attempt to recreate the beer, since I haven't found any modern versions to copy. But it's definitely worth trying.

Ulf Reese Næsborg - 2016-06-29 15:47:27

Have you seen this video, detailing the brewing process? There's nothing new or revolutionary in it, but at least it shows the tradition being alive (or, at least remembered) eight years ago. It's from Otterup on northern Funen. Let me know if you need something translated. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hku8dguRnTY

Lars Marius Garshol - 2016-06-29 15:52:25

@Ulf: No, I hadn't seen this one. Thank you! This is great stuff! I'm going to Denmark next week, and will make sure to get in touch with the local history society in Otterup.

Kristján Orri Sigurleifsson - 2020-09-07 21:18:52

HEJ LARS thank you for your great work in the field of kveik. I live in Denmark on the island called Als in south Jylland (the main towns are Sønderborg and Norborg) but I am not a Dane, I´m an Icelander. I am aspiring to starting a small nano brewery here on Als and really want to tie it into the local history as well as my own history. I saw one of your online talks, (Lallemand youtube channel) on Kveik, and there I saw your map of known farmhouse brewing traditions. Als has according to that map had its own yeast or at least its own farmhouse brewing history. I would love to know more about the brewing history of this area and also on the brewing history of Iceland.

THE BIG QUESTION: Can you point out where I could find some more info on the brewing history of Als or Iceland?

Thanks again for making Kveik great again ;)

PS I don´t have your book yet but will be buying it asap. Can´t wait to dive into that one.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2020-09-08 06:18:06

@Kristján: Every place that had grain farming has a history of farmhouse brewing, so Als is like the rest of Denmark in that regard.

The documentation I have for Als comes from Nationalmuseets Etnologiske Undersøgelser (NEU) and Afdeling for Dialektforskning at Copenhagen University. Both of these are archive collections that you need to visit in person to see any of the documentation.

I'm sure there will be published information from Als, too. For example, I found "Ølbrygning som husflid", Anne-Helene Michelsen, Sønderjysk månedsskrift, s445-448, 1975. It's about Aabenraa.

I would look at things published by the local history society: http://lokalarkivetials.dk/ Or at the very least talk to them and see if they have any ideas for where to turn. Also https://www.oksbol-lokalhistorie.dk/ And https://www.facebook.com/groups/1122722467755404/ Try your local library as well.

If you do manage to find anything and want to share I would be very happy for any pointers.

Regarding Iceland, as I understand it the Norse settlers had to abandon grain farming quite early, around 1000 CE, because of soil erosion. Once they didn't grow grain themselves any grain for malt will have to have been imported, which means very, very few people will have been able to afford it. I'm sure it has happened that people imported grain or malt and brewed, but it must have been very rare, and probably not sustained enough to create any tradition. Unfortunately.

Andreas Oxnæs Damgaard - 2025-09-05 14:35:22

The use of juniper is in fact attested far away from nefarious Swedish influence: it's in Hammerhum herred, Western Jutland.

[About how yeast was preserved between brews]:

The other method was to use a yeast ring, which was made of artificially cut and assembled small sticks, forming a tight wreath. (One such wreath is preserved in the Herning Museum.)

[…] There were also some who, instead of a yeast ring, used a juniper branch, and for that reason the juniper bush was also called "yeast-thicket" by many.

Den anden Maade var den, at man havde en Gær- krans, der var lavet af kunstig skaarne og sammensatte Smaapinde, saa det var en tæt Krans. (En saadan gemmes i Herning Museum.)

[...] Der var ogsaa nogle, som istedenfor Gærkrans brugte en Enebærgren, og Enebærbusken kaldtes derfor ogsaa af mange "Gærris".

Hardsyssels Aarbog, 1914, "Maltgøring og Ølbrygning", p. 103. Available here https://hardsyssel.org/bogarkiv/1914.html

Lars Marius Garshol - 2025-09-05 14:47:05

@Andreas: Thank you very much for this comment. I discovered this book some time after I wrote the above.

They are definitely using juniper, but I don't think this counts as using juniper as a spice in the beer. It's being used to preserve the yeast. (That's known from other places, too, outside of Denmark, although relatively rare.)

There are some other uses of juniper, too. Two Danish accounts say they used juniper infusion to clean the brewing vessels.

I still only know of the two mentioned cases where juniper is clearly being used as a spice, but I wouldn't be too surprised if there were more somewhere. (Would love to see documentation if so.) If it did happen I'd expect to see it in north Jutland somewhere.