Understanding farmhouse ale

Grain field, Tomter, Norway |

Somehow, the idea that farmhouse ale is a style of beer that began in "France and Belgium in the late 19th and early 20th centuries" has gotten traction. Many people have begun thinking of farmhouse ale as either saison or biere de garde. Which is strange, because this is bit like saying cheese is Danablu, and it began on a Friday afternoon in Denmark in 1953. So I guess the time has come for some clearing up.

Once farming began in northern Europe there was grain, and very likely, as soon as there was grain there was also beer. Archaeological finds indicate that initially, alcoholic drinks were probably a "grog" of berries/fruit, honey, and grain. At some point, the timing of which is not yet clear to me, the technologies for malting and mashing were developed, and there was beer as we know it today. Unhopped, but recognizably beer, made from malted grain as the sugar source.

Now, at this point, which at a guess would lie some time in the last millennium BCE (or possibly earlier, I'm still researching this) all beer was farmhouse ale in the sense that it was brewed on farms, for consumption on the farm. The area we are talking about now would be roughly from Brittany to the lower Volga, from the Alps to the Arctic Circle. Essentially, Europe north of the wine growing area, and south of the northern limit for grain growing.

The next step would be the formation of towns and cities. People living in urban areas have less space, and they cannot grow the ingredients they need for beer. But they would still need beer. So a specialization of work arose, whereby some people would brew more beer than they themselves needed, and sell it to those who did not brew. These would be the people later known in English as alewives, brewsters, and brewers.

Commercial brewery, Chiswick, London |

At this point, beer brewing split into two separate strands. One strand is the farmhouse brewing, which has continued up to the present day in surprisingly many places. The other strand is "normal" brewing, that is, all commercial brewing, as well as modern homebrewing, which essentially is a scaled-down version of the same tradition. The two did not remain 100% isolated, as borrowing of techniques from commercial brewing into farmhouse brewing can be seen in many instances, but the borrowing has been surprisingly limited.

What today is called saison and biere de garde is basically farmhouse brewing, as it existed in early 20th century Belgium and France, commercialized and scaled up. The reason the two styles are so hard to pin down is exactly because they are commercialized farmhouse ale, and farmhouse ale is alien to the whole concept of style, and wildly inconsistent from brewer to brewer. (I'll get back to why this is in a later blog post.)

A key point in understanding farmhouse ale is that it's people brewing for themselves, from their own ingredients, using the tools and techniques they inherited from their ancestors. And since the split-off point from commercial brewing lies so far back in time, these beers are very, very different from the commercial ones. Bizarre techniques like mashing for 24 hours, baking the malt into loaf shapes, not boiling the wort, reusing the same yeast for centuries, mashing with hot stones until you boil away all the water, etc etc etc seem so bizarre to people used to modern brewing because basically they come from another, parallel world.

A world in which, it should be added, beer was brewed for entirely different purposes. Brewing was commonly done for ritual occasions, such as religious feasts or family events like birth, death, marriage, etc. Some beer types were made for daily consumption, others for special uses like harvest ale. Beer in the farmhouse context was a lot more than just an alcoholic drink, in that it played a number of deeply important roles in social and religious life. (I'll have to expand on this, too, later on.) That aspect has typically changed in most places over the previous century, but to some degree it does live on in places.

Brewing on a farm, Tildonk, Belgium |

So when people today take up brewing on a farm but essentially take with them modern brewing techniques and ingredients to that farm, that in my view is something completely different from traditional farmhouse ale. Even if they do grow their own ingredients. Note that it need not be bad, but it's a completely different thing. It's not that the brewing takes place on a farm that makes farmhouse ale farmhouse ale.

Walking into a brewery, you can see at a glance whether it's a farmhouse brewery or a modern one. The brewing gear used is so different that a single glance is literally enough. Reading about farmhouse brewing techniques in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Georgia, and Russia it's clear that the farmhouse brewers in these places have a lot more in common with each other than with commercial brewers. Just looking at that video of Russian farmhouse brewing you see that, yep, this is farmhouse brewing.

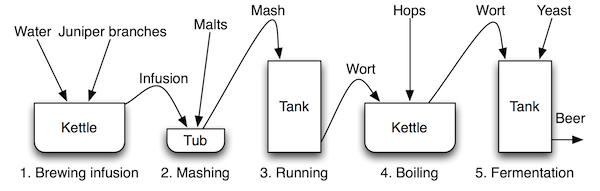

Norwegian farmhouse brewing process (boiled version) |

Above is a sketch of the basic Norwegian farmhouse brewing process (and equipment). There's huge variation even within Norway, but you can take this as a starting point for understanding the processes. The container in step 3 is called "rost" in Norway, "kuurna" in Finland, and "girine" in Lithuania. The details of its construction and use vary from place to place, but once you know the process, a glance at a photo of a Lithuanian farmhouse brewery is enough to tell you which vessel is used in step 3.

Lithuanian farmhouse brewery (girine on far right) |

It could be argued that, strictly speaking, saison and biere de garde as you know them are not farmhouse ales. They are farmhouse ales that have been imported into the world of commercial brewing, undergoing some changes on the way. And we should all be glad that this happened, because otherwise these styles would be totally unknown to the beer world, which would then be a much poorer place.

And, one day, the same thing may happen to maltøl, sahti, gotlandsdricka, and koduõlu, which would be a major enrichment of world brewing culture. It already has happened to kaimiškas, but only in Lithuania, and since nobody goes to Lithuania, nobody knows about it. Yet.

Similar posts

Up and coming beer destinations?

The subject for this month's The Session was: "What are the up-and-coming beer locations that you see as the next major players in the beer scene?" Well

Read | 2015-03-06 18:04

What counts as a farmhouse ale?

The most common question I get in interviews is "what do you consider to be a farmhouse ale?" and since the answer is a little involved I decided to write it up more fully

Read | 2020-07-26 14:52

Farmhouse ales of Europe

Having surveyed the state of farmhouse brewing in Norway it's time to look at the same thing in Europe generally

Read | 2014-10-18 16:46

Comments

Marshall - 2015-03-11 18:03:17

What a great read! I'm curious what you have to offer about traditional Latvian brewing, as that's where my wife's family is from and I'd love to attempt some classic techniques. Cheers!

Lars Marius - 2015-03-12 03:08:06

@Marshall: Thank you! Unfortunately, the Latvian tradition is the least-known of all of these. I've summarized what little I know here: http://www.garshol.priv.no/blog/305.html I'm hoping to be able to travel there this summer and learn more. If I do I will definitely write about it.

A little bit more exists in written sources, but in German only, I'm afraid.

Matt - 2015-03-12 13:03:33

Wow, another wonderful post! I can't wait to hear more about the traditional brewing methods.

Ron Kaufmann - 2015-03-15 10:37:19

Lars, I like your take on farmhouse beer, especially from a European perspective. It's nice to know that traditional farmhouse brewing survives to this day, and is not constrained by certain styles. Here in the U.S. everything must be defined and fit into certain styles. Even so much so now that farmhouse beer and farm breweries have been classified as two distinctly separate entities that can exist without the other. See this article http://www.foodrepublic.com/2015/03/03/deciphering-craft-beer-terminology-farmhouse-vs-fa

Lars Marius - 2015-03-15 11:25:14

@Matt: Thank you. If you work backwards on the blog you'll find a good bit of documentation of brewing methods.

@Ron: That's the very article that provoked this blog post in the first place. :)

Simonas Gutautas - 2015-04-02 10:25:00

There is nice Linda Dumpe study on latvian beer. Released in 2001 as book it has english summary. I can scan it and send you. If you wish.

http://labsalus.lv/alus-tradicijas-latvija/

Lars Marius - 2015-04-03 10:50:33

@Simonas: That would be fantastic! Thank you so much! :-)

jerry - 2021-04-02 22:39:44

that low key but super true dig at lithuania haha

Dan Pixley - 2022-05-21 09:56:13

I am curious if your view has shifted on this at all in the last 7 years?

Lars Marius Garshol - 2022-05-21 10:04:06

@Dan: Some things have shifted. I no longer believe "Nordic grog" was typical of early beers. I think early beers were just that: beers. I also think true, full beer brewing arrived together with agriculture, and that the methods of malting and mashing were invented in the Middle East more than 10,000 years ago.

Also, I guess the last bit, that nobody knows about Lithuania, isn't quite as true any more.

Other than that I don't think I've changed my mind about any of this.