Norwegian brewing processes

Barley field with some oats. Søgarden, Rælingen. This is in "flatbygdene". |

I've collected enough evidence now that I'm beginning to get a picture of farmhouse brewing as it was practiced in Norway in the past. However, to understand how people brewed we have to start with the geography, because that determined everything else. The brewing was a tradition descending in unbroken line from the Stone Age to the present. There were lots of changes on the way, and these were transmitted from village to village. When you look at the resulting patterns on a map it's obvious that the geography was tremendously important for what influences went where.

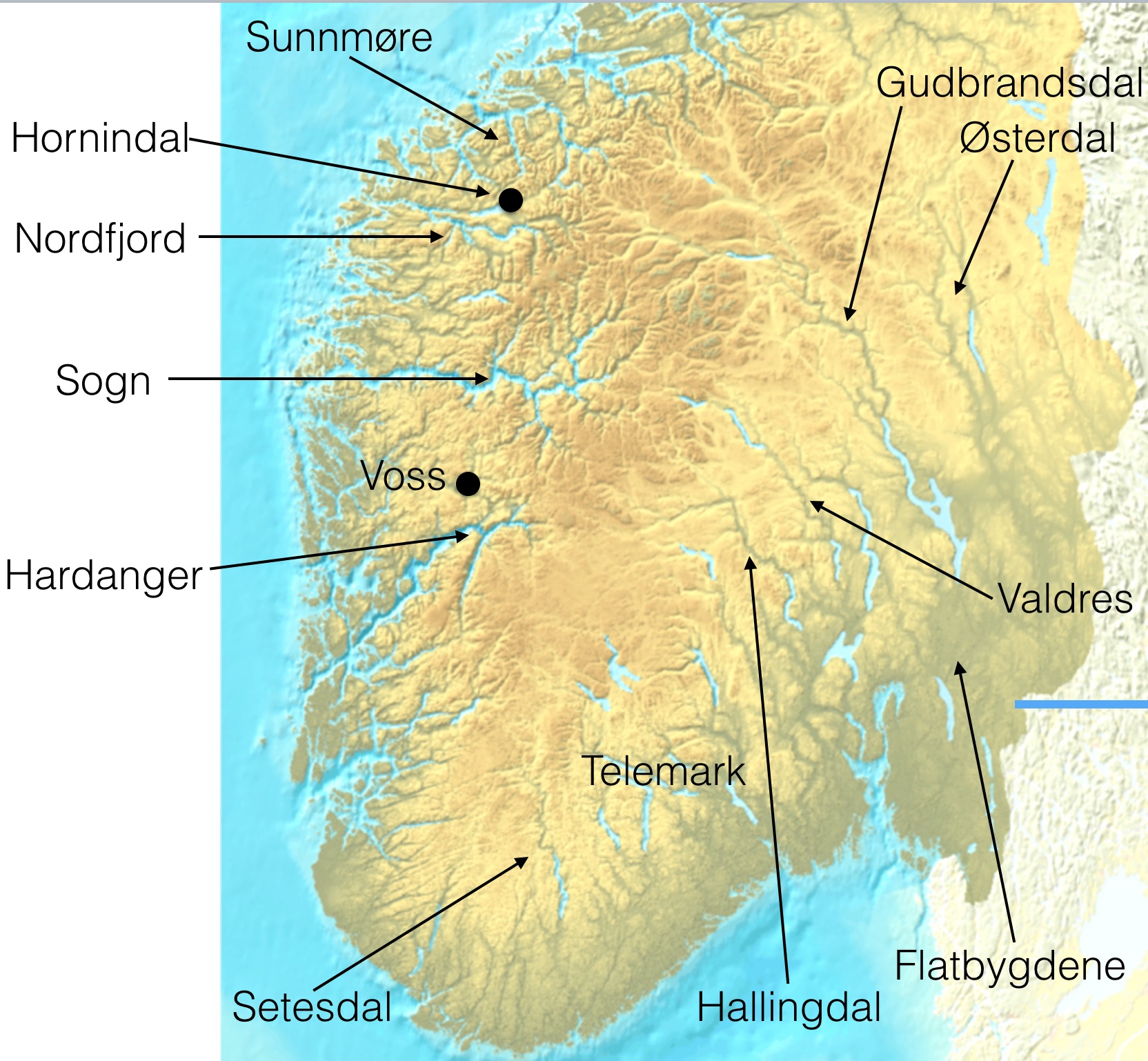

So let's look at a map. It's pretty detailed, so click on it to see the full thing.

Southern Norway, topographic map |

Let's start with the green bits in the south-east. This area is known as "flatbygdene", literally "the flat villages." It was so called because the terrain here was not flat, but just hilly, unlike the rest of the country, which is mountainous. All the yellow and brown stuff in the centre is mountains. If you fly over that part of Norway it looks like nobody lives here. And to a pretty good approximation that's true outside the areas marked in green.

However, you see some furrows of green in the yellow. Those are valleys, and that's where people live outside of flatbygdene. You see I've marked the main valleys with their names. You'll be hearing more about those later. In the west it's kind of the same story. Out by the coast the land is fairly flat, but also weatherbeaten. Then the mountains rise, and people live mostly along the fjords.

So, you can break southern Norway up as follows: the eastern part, which is flatbygdene plus the valleys. The southern part, which is the greenish fringe along the south coast. The western part, which is along the coast and the fjords. Separating these are the mountains, which is really the biggest part, but nobody lives there.

Along the coast growing grain was difficult so for our purposes the fjords is really the important part. And here there are several distinct areas separated from one another by mountains. Let's go south to north: Hardanger, Sogn, (Sunnfjord), Nordfjord, Sunnmøre. The biggest divider here is between Sogn and Sunnfjord/Nordfjord: the largest glacier in continental Europe.

Hjørundfjord, Sunnmøre |

The final thing you need to know is that north of the blue line on the lower right hardly anyone lives in central Sweden. If you drive through that area today there's just miles and miles and miles of pine forest and lakes, but hardly any houses. So north of that point there was little contact across the border.

The big picture

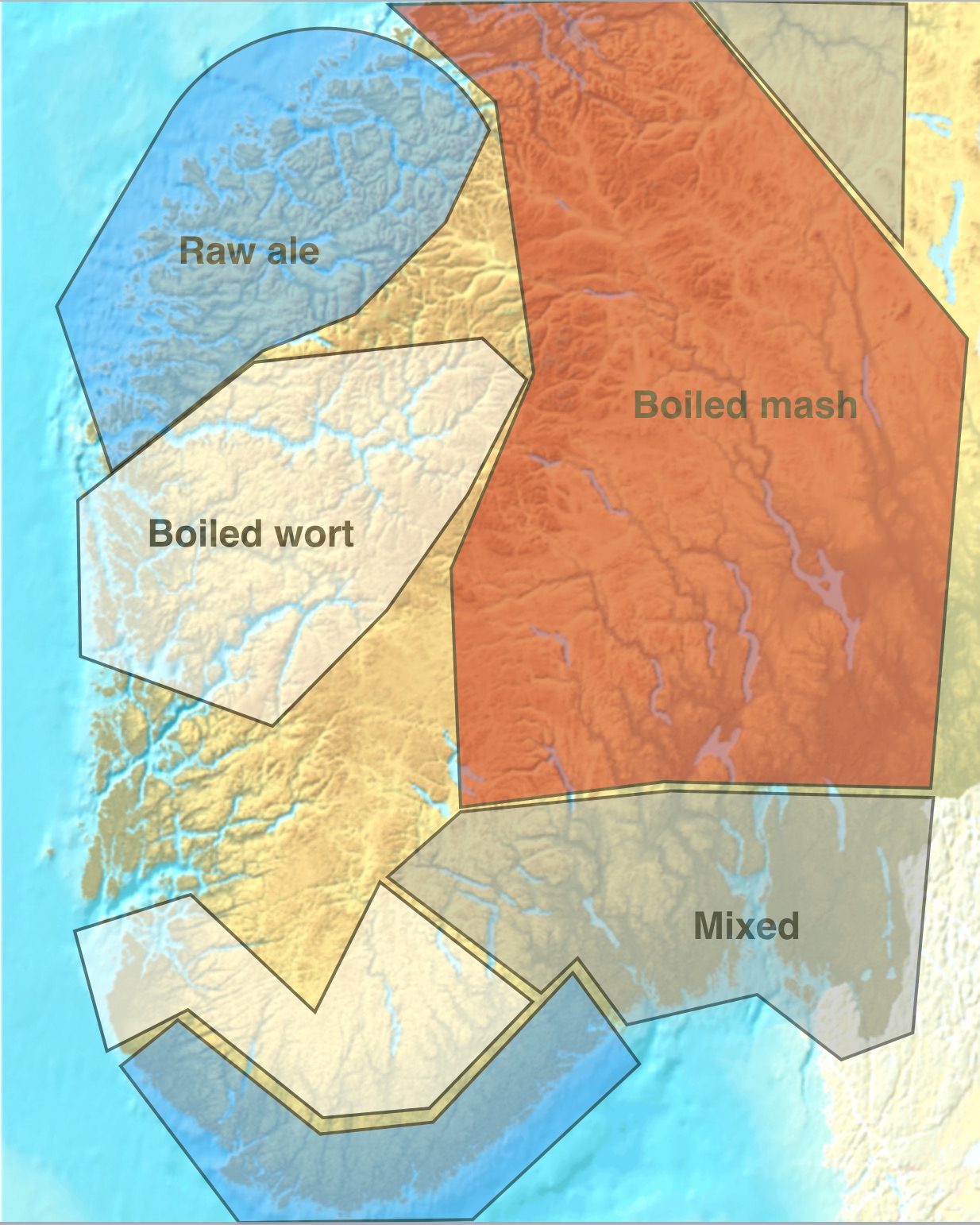

My attempt to summarize the brewing processes used can be seen below. It's kind of rough, and in parts the data is either missing or weaker than I'd like it to be. Still, it gives an idea.

Southern Norway, brewing processes |

The big red area is the area where people would usually boil the mash, and also boil the wort. This means exactly what it says. They'd heat the mash in the kettle and keep going until it boiled. Then they'd transfer to the strainer, run off, then boil the wort. It's obviously similar to decoction mashing, but not exactly the same.

Now, how this brewing process came to appear in exactly this area I really don't know. There's no obvious place for it to have spread from that would make you expect this shape. Yes, it may have come from Oslo, but if so, why did it nearly only spread north? For now this question will have to be left open.

The two gray areas are mixes of many different processes. I think the lower one was caused by contact with Sweden, and the raw ale belt along the coast. Probably. The upper one I'm not sure of. It continues all the way up to the Arctic Circle.

The big white area is an area where they boiled the wort. What was historically the biggest city and the main trade port of Norway, Bergen, is on the southwestern edge of that area. So it seems pretty likely that the practice of boiling the wort spread from there. The southern white area contains the other major city and port of Stavanger, so it might be a similar story there. What's in between the two I'm not sure of.

The two blue areas are raw ale areas. The one along the coast could be caused by contact with Denmark, which was mostly raw ale. The northern one was probably caused by simple isolation. The glacier separates it from the boiled ale area in Sogn to the south, and the Sunnmøre alps separates it from the boiled mash area to the north.

I suspect the boiled mash area extends all the way to the coast in the north because contacts from the north end of Gudbrandsdalen down to the coast were fairly good here. There are other brewing culture markers that indicate the same thing.

But on what evidence am I claiming this? Let's dive a little deeper.

Lars Olav Muren adding the hops, Norwegian Folk Museum |

Zooming in

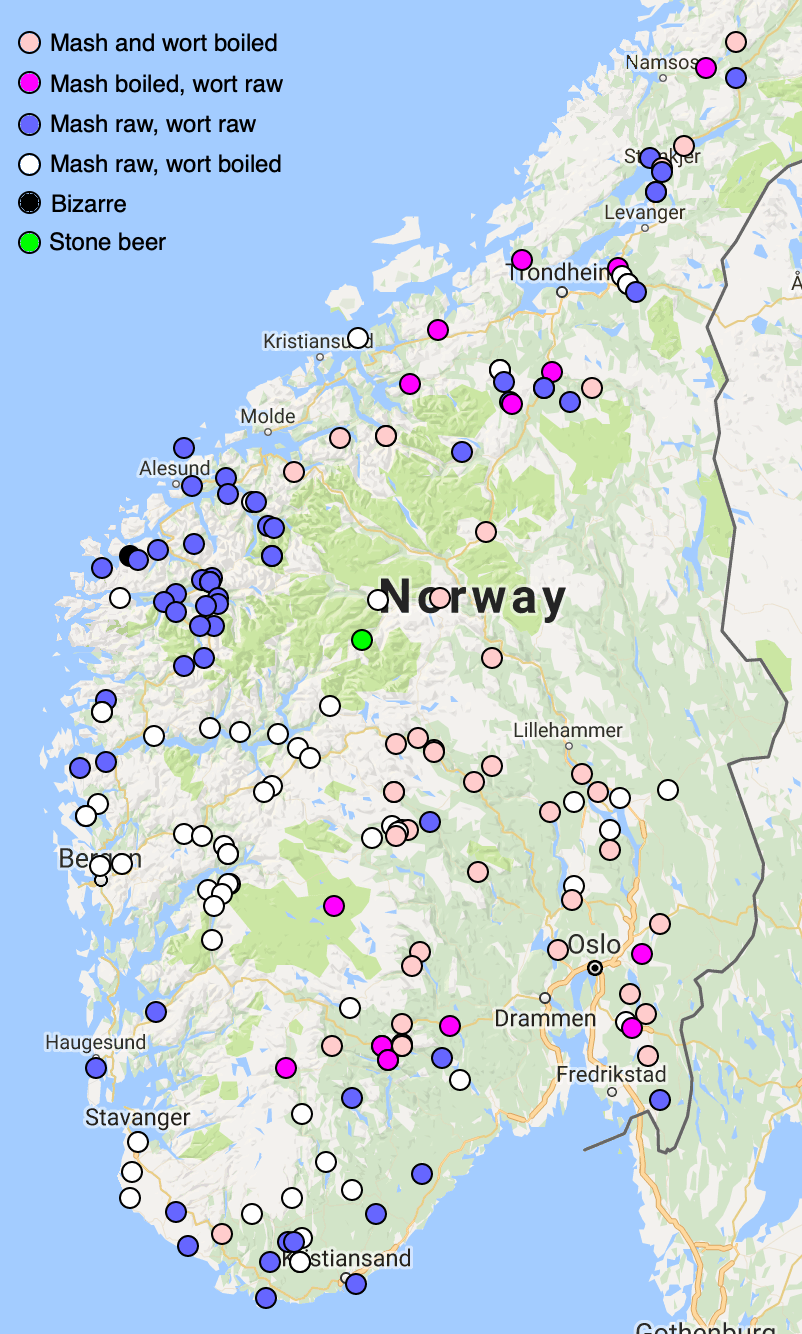

The brewing processes used in farmhouse brewing are an unbelievable tangle of crazy madhat tricks. People seem to have used pretty much any process that could potentially lead to alcohol being produced from grain, and quite a few processes that I honestly had never imagined. I've gone through the documentation I have (see "Sources" below) and classified the brewing processes used in detail. That gave me 118 different processes, but they often differ only in very minor details.

That's obviously too much to make sense of, so I started grouping them into a more coarse-grained classification. In order to wind up with something that could actually be visualized and comprehended I have decided to ignore some process variations. My criterion here was to isolate the processes I think affect the flavour the most. Since I've never tasted many of these processes I'm working partially blind here. It's possible that this classification will have to be redone later.

These are the things I've ignored:

- When, how, and if the hops were added.

- Cold mash. This means leaving the ground malts in cold water for hours. (Example: Morgedal.)

- Step mash.

- Mashing in the kettle. So, basically, raising the temperature of the mash not by adding hot liquid, but by heating the mashing vessel. (Example: Morgedal.)

- Remashing. This is where you run off wort, heat it, then pour it back on.

I've also ignored some rare and strange tricks, like boiling with the lid on, splitting the wort several ways then doing strange things with it, etc etc.

The resulting classification breaks all brewing processes into six groups. If we simply plot these on a map we get the following.

Southern Norway, brewing processes |

I guess this walkthrough leaves people with lots of open questions. Please feel free to ask in the comments. I'll try to answer as best I can, and it will also help me decide what blog posts to write next.

Sources

The main source for this is the farmhouse brewing questionnaire from Norwegian Ethnological Research. That consists of 181 individual responses totalling 1228 pages. Each one of these describes the brewing in a single place as documented by someone who's either brewing him- or herself, or who's interviewed old people in the area. There probably are some errors in some of the responses, but in aggregate they present a fantastically detailed and uniquely reliable picture of farmhouse brewing as it was in Norway.

I've supplemented this with 110 individual accounts of brewing in specific places in Norway. These come from brewers I've visited, brewers I've interviewed by phone or email, old folklore books, local history society journals, unpublished manuscripts, and so on. How many pages this is is hard to estimate, so I don't really know.

Frustratingly, the accounts tend to cluster geographically, so that some regions (Nordfjord, for example) are documented in near-perfect detail, while other regions are simply blank. The region along the border with Sweden, for example. Vestfold. Sunnfjord. Northern Norway. And so on. So I'm not done yet.

Similar posts

Norway: climate and ingredients

Norway may not be the world's biggest country, but it has considerable geographic variation

Read | 2015-05-19 10:53

Traditional malting in Morgedal

The guys I visited in Morgedal were definitely brewing traditional farmhouse beer, but they bought the malts

Read | 2015-11-21 13:09

Norwegian farmhouse ale styles

People are confused over what to call Norwegian farmhouse ale and what styles there are

Read | 2017-01-19 19:23

Comments

Ed - 2016-12-11 14:59:27

Excellent work!

┼smund M. Kvifte - 2016-12-12 09:21:00

The areas you have assigned for different brewing traditions fit surprisingly well with a map of Norwegian dialects. (e.g. https://snl.no/dialekter_i_Norge). Especially on the western coast, it seems brewing and ending vowel in infinitives follows each other. It could maybe suggest the differences between brewing methods being quite old - if brewing and dialects follow the same lines, people traveled in the same way when the dialects formed as when the brewing traditions formed. Although I am no historian of Norwegian infrastructure, I believe major inland road projects started in the 1800s.

The other main variables than geography, I think would be the wealth of the farm, and the equality/inequality of the village. On a rich farm, they would likely have better access to good coppers to boil in.

More egalitarian areas would likely have more uniform brewing traditions. It would be interesting to look into if farm size and wealth have an effect... Tax records would be worthwhile to look at.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2016-12-12 09:43:47

@┼smund: Haha! That's really cool. :) The match isn't perfect, but I agree it's surprisingly similar. I take that as a small validation of the work and the method.

I'm convinced the brewing method differences are old. Wille's description of brewing in late 18th century Telemark matches 19th century brewing in the same area perfectly. Wilse's description of 18th century Spydeberg does the same. An 1898 description of brewing in Granvin is near-identical with how people in Voss brew today. I'd really like to find Str°m's description of 18th century brewing in Nordfjord, because I'm convinced he's going to describe a raw ale.

I see the same thing in the Baltics. Late 18th and early 19th century descriptions of the brewing are astonishingly close to the present-day brewing.

As far as road building goes I think you are right.

The wealth of the farm definitely did affect the brewing, but it would typically affect what grain was used, how much of it, how often they brewed, and what sort of equipment they had for malting. A poor cottar might dry his malts in the sun or in a kettle, while a rich farmer would have a badstu.

It seems that coppers were very expensive in the 15th century, but that most people had access to them around the mid-16th century. It's possible that wort boiling was common among richer farmers before this, and afterwards spread to the poorer ones south of the Jostedalen glacier.

Possibly the same thing happened in the east. Brewing stones seem to have been the most common in the east, and it may be that this is where the mash boiling comes from, because that's what happens when you brew with stones.

Your point about the effect of equality is very interesting. I hadn't thought of that, but it's a valuable point. Hmmm....

Andreas S - 2016-12-12 14:40:20

Perhaps if you included time/dates on the brewing methods plot it would yield some more information. Could it be f.ex that the raw/raw method was prevalent before some hanseatic trader brought the raw/boiled method to Bergen?

Lars Marius Garshol - 2016-12-12 14:45:16

@Andreas: Good point. I should have made this clear. Every single piece of information dates from 1890-2016. So we have very little idea how people brewed before that. There are some late 18th century accounts that show pretty much the same methods, but that's it.

Ben Acord - 2016-12-13 21:46:48

Can you go into some detail about the part of the country that boils their mash and then boils the wort. I'm curious as to why what does that do. You have a fantastic site. I am working my way through site from the beginning

Lars Marius Garshol - 2016-12-14 02:08:17

@Ben: Thank you! :)

The problem with the part of the country where they boiled the mash and the wort is that the brewing appears to have died out there. So as far as we know there is no beer to try, and no brewer to learn from. I'm still working on that, but I guess what I could do is to build a blog post around an old recipe.

Bosh - 2016-12-19 11:03:44

So by boiling the mash do you mean they'd boil the mash grains and all? Damn. Didn't think I'd ever see that.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2016-12-19 12:27:05

@Bosh: Yes, that's exactly it. I don't know what it did to the flavour. I'm trying to find someone who still brews that way, but no success so far.

scheer - 2021-09-29 18:03:09

bonjour vos livres sont ÚditÚs en franšais et si oui, ou peut on les trouver d avance merci et fÚlicitations pour votre travail sur le kveik cordialement de France

Lars Marius - 2021-10-06 09:14:31

@Scheer: Unfortunately there are no translations to French yet. I have not heard of any being in progress either.

Nick Smith - 2022-03-22 04:24:22

Thanks so much for this Lars. I've been brewing ales with Kveik and have been trying a speculative version of a remash, that is, I run off a normal wort from the mash, boil the wort, then pour it back onto the mash again, let it steep from boil to pitching temp, strain the mash and pitch the wort with Kveik. I'm getting similar gravities for lower ABV ales to an hour's boil with much less loss of wort as boil-off. Is this mega-speculative and a departure from the Norwegian tradition or perhaps not as outside the mothership as it first sounds? I read the extract from Odd Nordland where he mentions "Rosten" and repeated pourings of the boiled wort back onto the mash too. Cheers mate.

Lars Marius - 2022-03-22 08:01:53

@Nick: Letting the mash cool to pitch temperature is very unusual, but the basic idea of the remash was a fairly common process in eastern and central Norway. So it's not that far off, no.

They don't seem to have used kveik in eastern Norway, though, but to have had a related type of yeast.