Celtic Beer Yeast and Blue Cheese

The center of Hallstatt, Bwag, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

A recent archaeological find caused much stir and writings in various newspapers, but everyone seems to have missed the most interesting part of the discovery. However, before we get to that, let's have a little look at the context.

The find was in Hallstatt, Austria, which is an interesting place in a number of different ways. The culture that later came to be known as the Celtic culture arose out of the so-called Hallstatt culture, which seems to have developed in the area around Hallstatt. Today we associate the Celts with Brittany in France and the northwestern edges of the British Isles, but basically that's where the Celts remain today, after having been pushed to the edges of the continent by Latin and Germanic peoples.

Map showing location of Hallstatt. |

Hallstatt was an important place in prehistory because of its salt mines, which were in operation at least from the 14th century BCE up to the present day. Salt was a highly valuable commodity back then, and so while most places in Europe were peopled by farmers, Hallstatt was a mining community.

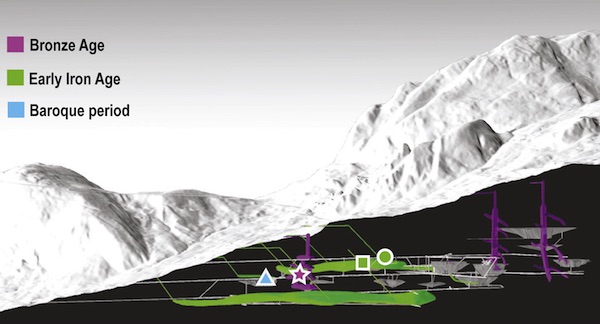

The sample locations inside the salt mine, figure 1B from the paper in Current Biology. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. |

The salt mines are very interesting archaeologically, because the high salt content and low, constant temperature preserve organic remains very well. The mines have dense layers of waste that are many meters deep, and from these all sorts of interesting artifacts have been excavated.

In this particular case, however, the archaeologists chose to focus on human excrement, because of what it can tell us about the diet of those who produced it. They analyzed four samples, from 1200 BCE, 600 BCE, 600 BCE, and 1750 CE.

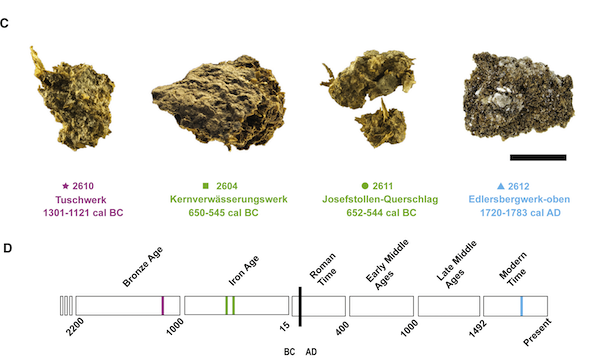

The four samples, placed on a timeline. Figure 1C and 1D from the paper in Current Biology. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. |

What caused all the headlines was one of the samples from 600 BCE. Specifically the second from the left in the image above, number 2604.

The researchers analyzed the DNA they were able to find in the samples, in order to get a picture of the gut microbiome of human beings at various points in history. They also looked at remains of various kinds of food etc.

What they found was mostly cereals, specifically barley and spelt, which is not surprising at all, since we know that historically farmers got most of their calories from grain. The miners probably bought most or all of their food from nearby farmers. A little beef and pork was also found. And in the DNA, Penicillium roqueforti showed up, which together with other evidence gave reason to suspect the miners had been eating blue cheese in 600 BCE.

All of which is quite interesting, but of course what we care about is the beer find.

What the researchers found was DNA belonging to beer yeast, specifically Saccharomyces cerevisiae, also known as ale yeast. (They did not find lager yeast, as some media have incorrectly reported.) Of course, this could be from leavened bread, or from beer, or from wine, or simply wild yeast from the air. But the DNA contains clues to what sort of yeast it was.

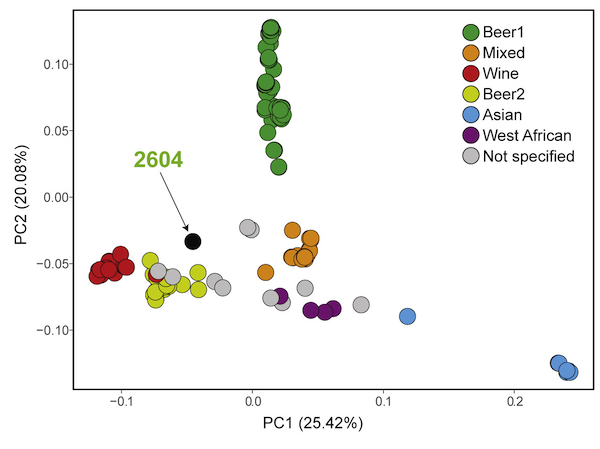

Analyzing the genome of the yeast they found that it matched wine yeasts (47%), beer yeasts (29%), and wild yeasts (19%). Using a clustering method (see below) they found it grouping itself with the Beer 2 yeast group. Which as we know has the Wine group as the nearest neighbour. So that made them think this might be a beer yeast.

Clustering result from using principal component analysis on the genomes. Figure 4E from the paper in Current Biology. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. |

Checking specific genes they found that their yeast had the RTM1 gene, which protects yeast against high sugar concentrations. This gene is very common in beer yeasts, for obvious reasons. They also looked for the gene regions A/B/C, which are usually present in wine yeast, and the yeast didn't have them. That means it's unlikely to be a wine yeast.

And we've already seen that these miners were clearly consuming a lot of barley, so they did have what they needed to brew beer. There is also a beer find from Switzerland dating to around 3900 BCE, so beer brewing had already been known on the north edge of the Alps for a very long time.

In short, it seems a fairly safe bet that this was a beer yeast.

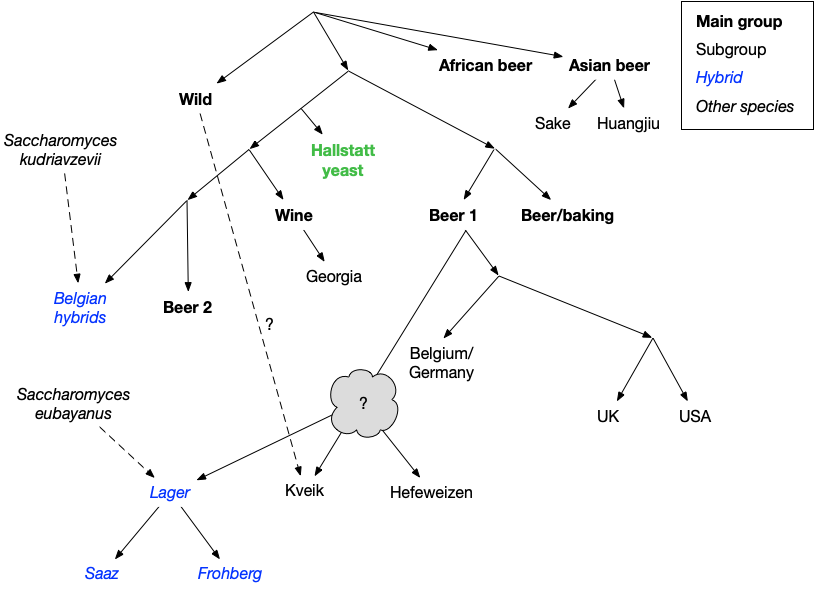

It gets more interesting than that, though, because since the researchers had the full genome of the yeast, they were able to insert it in the yeast family tree from Gallone 2016. Which means we can tell where this yeast belongs relative to the yeasts we are using today. So here I am going to build on the tree I published in the previous blog post.

My drawing of the yeast family tree, with the Hallstatt yeast inserted. Look for the green text in the middle. |

Surprisingly, it turns out to branch off just above where the Beer 2 and Wine groups separate.

This could mean that it belongs to a group of domesticated beer yeasts that since went extinct. We have, after all, lost most of the beer yeasts that Europe used to have, so this is entirely possible.

I suppose it could also mean that this is a snapshot of what the Beer 2 yeasts looked like in 600 BCE. If the descendants of this yeast had gone through 2400 more years of evolution it's possible it would have looked like the Beer 2 yeasts do today. I think.

But that's not the biggest thing we get out of this, in my opinion.

The key thing is that this seems to be a domesticated yeast. In 600 BCE.

Bronze vessel for unknown purpose from Hallstatt. NearEMPTiness, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

There was already strong evidence in documentary sources that people in Europe and Egypt had started deliberately reusing yeast before 0 CE (my book, page 106), and now we have strong genetic indications that deliberate reuse of yeast in Europe began long before that. For this yeast to be domesticated by 600 BCE, domestication must have started quite some time before that.

How long before did people begin reusing this yeast? We don't know. What we do know is they had been brewing in this area for millennia already, so yeast reuse could be very old indeed. How old nobody knows. Yet.

As the farmhouse brewers have shown us, technologically yeast reuse requires nothing more complicated than a piece of wood (my book, most of chapter 4). Of course, you also need the idea of reusing the yeast, and to know how to do it right, but there's no reason people long, long before 600 BCE cannot have had both the idea and the know-how.

I think the other main thing you should take away from this study is that yeast genetics has made unbelievable advances over the last few years. Six years ago we didn't even know of the existence of yeast groups like Beer 1 and Beer 2, and now suddenly we can take prehistoric yeast and make a meaningful genetic comparison with today's yeast.

It seems fair to assume that research over the next years is going to reveal a lot that we presently don't know, and don't even suspect. I for one am definitely looking forward to it.

Similar posts

The Early History of Hops

One of the biggest mysteries in the history of beer is where and when people started using hops in beer

Read | 2022-12-06 10:15

Kveik analysis report

One of my goals for the Norwegian farmhouse ale trip was to see if kveik (family yeast) still existed in Norway, and to get samples if possible

Read | 2014-09-26 08:11

The Yeast Family Tree Grows

A few years ago I wrote about the groundbreaking study (Gallone et al 2016) that for the first time gave us an idea of how the different types of brewers yeast are related to each other

Read | 2021-10-26 10:39

Comments

Dave Richards - 2021-11-01 09:07:09

Very scholarly, thanks. Which of your blogposts can I read to help with your comment "technologically yeast reuse requires nothing more complicated than a piece of wood"? Many thanks, Dave

Lars Marius - 2021-11-01 09:21:23

@Dave: I haven't really described that in any blog post, in part because the full argument gets too involved for that. Chapter 4 of Historical Brewing Techniques is in a way about this specific issue, so your best bet is basically to read that chapter.

Thomas - 2021-11-01 10:28:51

Very interesting! If the full genome is available, how difficult would it be to bring the 600BCE-yeast back to life?

Lars Marius - 2021-11-01 10:30:05

@Thomas: That's a very good question. I think the answer is that it would be so expensive that it's very unlikely anyone will actually do it.

John - 2022-07-28 01:32:21

How difficult can reviving be? Take a living yeast cell. Pull out all of its DNA. And replace that with the old DNA. Presto, you have a living cell starting to behave as the old strain.

Lars Marius Garshol - 2022-07-30 11:27:19

@John: Inserting a whole genome into a cell and bootstrapping it from there has been done. The first time was in 2010, with a bacterium. Yeast might be harder, for all I know, but even if anyone knew how to do it, it is definitely far too expensive.