The Yeast Family Tree Grows

Test fermentation columns at the Lallemand lab in Montréal, Canada. |

A few years ago I wrote about the groundbreaking study (Gallone et al 2016) that for the first time gave us an idea of how the different types of brewers yeast are related to each other. It was progress in genetic technology that made the study possible, and in the years after more studies have come out, giving us an even better picture of the family tree of yeast. So I figured it was time for an update.

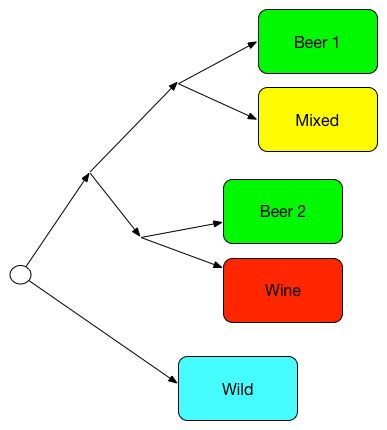

In case you didn't read about that study, it sequenced 157 strains of yeast, then organized them genetically into a tree according to how closely related they were, and found that they all fit into these groups:

Simplified family tree, redrawn after Gallone 2016. |

In short, nearly all beer yeasts you've ever heard of belong to either the Beer 1 or Beer 2 groups, plus a couple in the Mixed group.

Chinese origin

This paper reports on a giant project where they sequenced the genomes of 1,011 yeast strains. The original Gallone 2016 study focused mainly on beer yeast, but this study has a much wider selection of yeast types. It still reproduced the same groups as the Gallone 2016 study, but it also added many new groups.

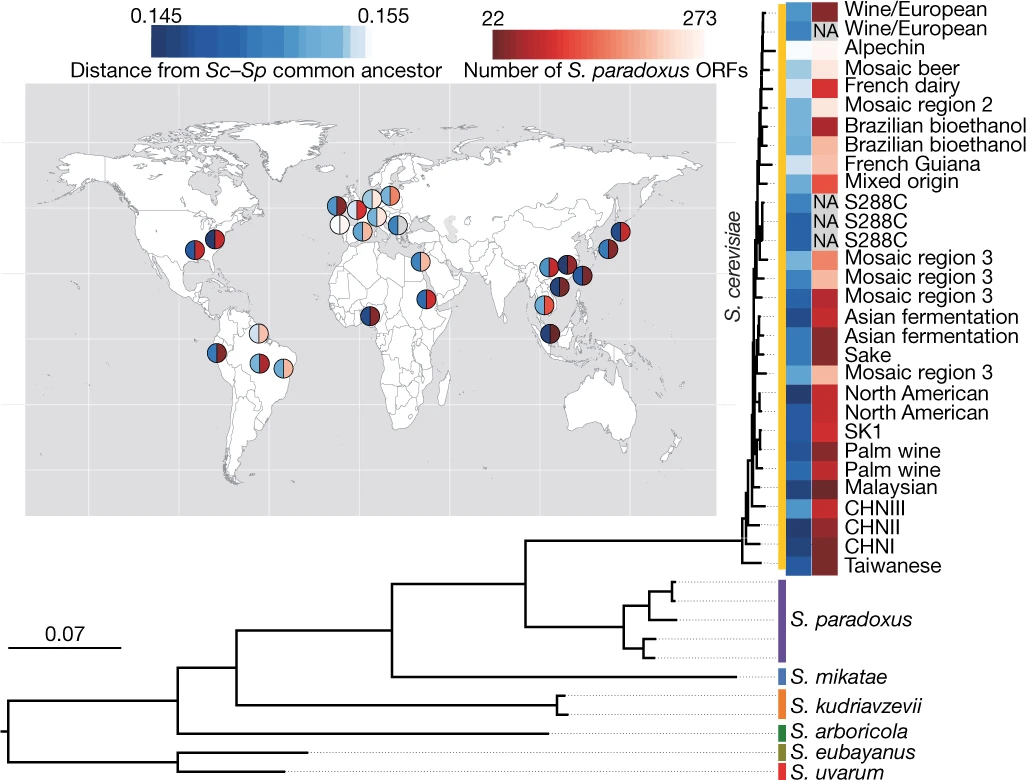

Figure 2 from the paper in Nature, unmodified. CC BY 4.0 license. |

The first interesting result they found was that the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, that is, brewers yeast, originated in what is now China. If you look at the diagram above you see at the bottom the other species in the Saccharomyces family, and then above them the various groups of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts.

At the root are three groups of Chinese yeasts (CHN I to III) and a Taiwanese group, which is strong evidence that the species originally evolved in China.

Another study published the same year looked at wild yeasts from China, and found that they had much greater genetic diversity than wild yeasts from any other region. That, too, is strong evidence that China is where the species originated.

Looks like that issue is settled.

Sake and huangjiu yeast

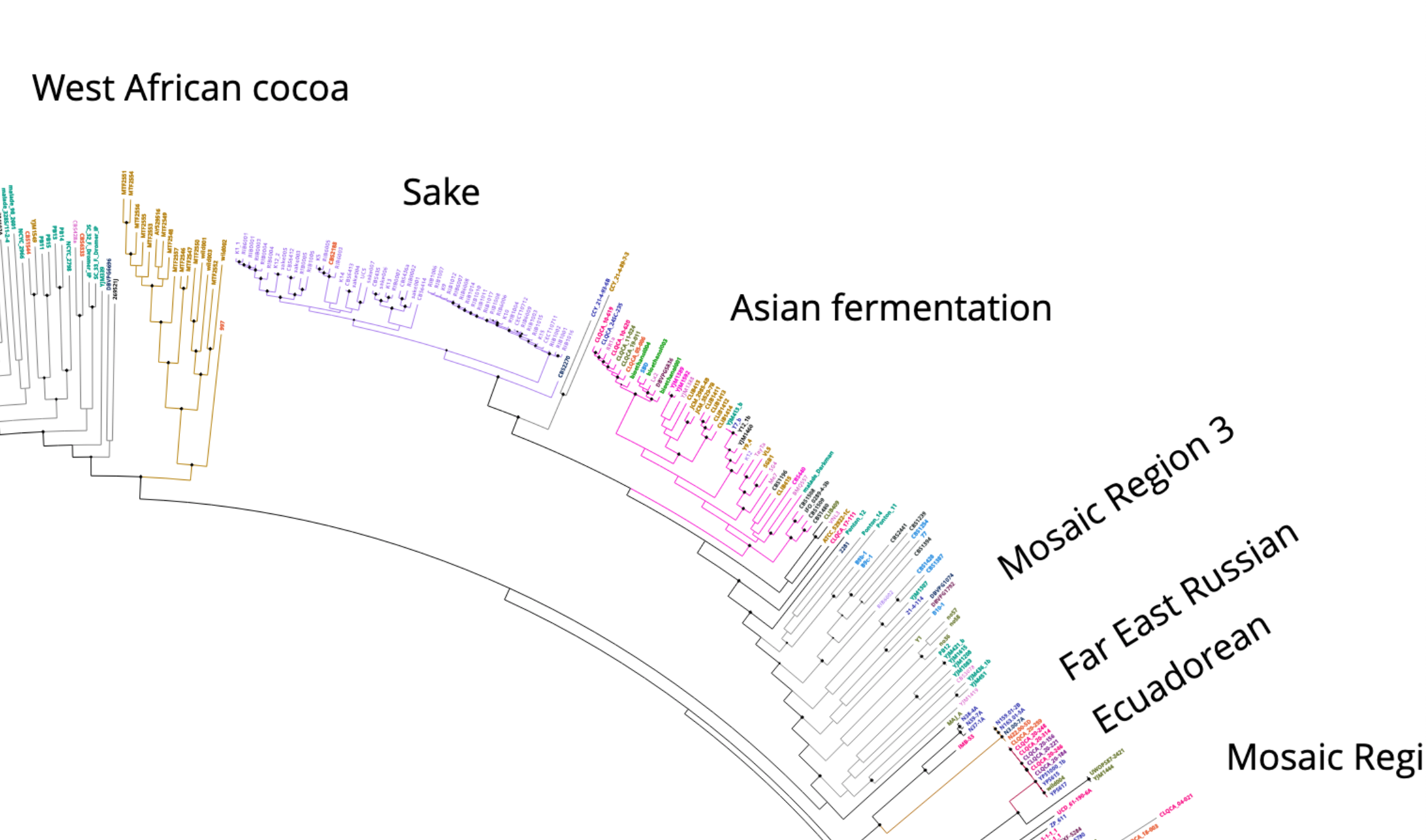

Part of genetic tree rendered by Kristoffer Krogerus, by combining the 1,011 yeasts with the ones from Gallone 2016. "Asian fermentation" here really means huangjiu, I think. (Image reused with permission.) |

The 1,011 yeasts study identified Japanese sake yeasts as a separate genetic group, which is interesting, although not unexpected. What's interesting is that both of the studies above find that it is a subgroup of Chinese huangjiu yeasts.

Huangjiu could be described as the native Chinese type of beer. It is like sake in that instead of being based on malt, it's made with a mold which breaks down starch in the grain to sugar, and the mold works together with a yeast to ferment the sugar to alcohol. Huangjiu, however, can be made both from grain (millet, wheat, barley, etc) and from rice, while sake is made from rice. This is probably because north China is mainly a grain-growing region, while the south is rice-based.

What's interesting about this is that it suggests the Chinese domesticated a yeast for brewing, and that this yeast then travelled to Japan and evolved into sake yeast there.

This is very similar to the pattern we saw with brewers yeast, where continental domesticated brewers yeast first travelled to the UK, then from there to the US. And also similar to the way the same yeasts seem to have travelled to Norway and evolved into kveik. In other words: once brewers got hold of a yeast strain they liked, they seem to have hung onto it. And to have hung onto it for many centuries.

Other new yeast groups

Georgian food and wine, St. Petersburg, Russia. |

The 1,011 study also identified some other interesting groups. For example, inside the wine group they found a subgroup of Georgian wine yeasts. Which makes sense, since Georgia probably has the oldest continuous wine tradition on earth. Georgia also has a huge number of indigenous wine grape varietals native to Georgia.

They also found a separate subgroup of African beer yeasts, which is very interesting. Africa has an enormous variety of traditional farmhouse brewing going on in many different countries over much of the continent, and many of those brewers still maintain their own yeasts. (Martin Thibault spoke about Ethiopian brewers and their yeast at Norsk Kornølfestival in 2020.) Now it looks like they, too, have their own genetic subgroup of yeasts.

If you're interested in diving further into these results, Kristoffer Krogerus has an excellent blog post with a family tree that combines the Gallone 2016 yeasts with those from the 1,011 study.

Belgian hybrids

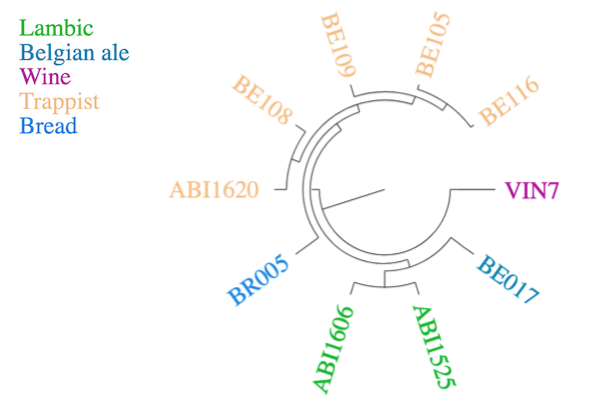

The tree of the S.cer x S.kud hybrids, rendered by yours truly. |

The team that did the Gallone 2016 paper have been collecting even more yeasts than were in that paper, and in 2019 they did a new paper focusing on the hybrid yeasts they found. And one of the surprises in this paper is how many hybrids there actually are among the brewing yeasts. As we all know, lager yeast is a hybrid, but they also found ale yeast hybrids, particularly in Belgian brewing yeasts.

These yeasts are hybrids of brewers yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and a much less-known species, Saccharomyces kudriavzevii. S.kud for short is a cold-tolerant species that's mostly been found on oak trees, and which seems to exist only in Europe and Asia in two separate wild populations.

The odd thing is that apart from one wine yeast and one bread yeast, all of these S.kud hybrids are Belgian brewing yeasts. Most are from Trappist breweries, but some were isolated from lambic. There are actually two separate genetic groups, interestingly, and the lambic yeasts turn out to have higher acid tolerance than the Trappist yeasts, which makes sense.

But note the implication! People believe that the yeasts which ferment lambic are all wild, but earlier studies did not actually find the S.cer yeasts any other place than in the barrels. And now we find that not only are these yeasts domesticated, but they also seem to be adapted to lambic brewing. It's beginning to look like those people who claimed lambic brewers actually have house cultures living in the barrels were right.

The S.cer part of the genome of these yeasts turns out to belong to the Beer 2 group, which is interesting, because Beer 2 mainly consists of yeasts that are used in Belgian brewing. Saison yeasts belong to this group, for example. There are also some English ale yeasts in there. Beer 2 is closer to wine yeasts and is generally seen as less domesticated than the Beer 1 group.

New details on lager

The other kind of hybrid that the Gallone 2019 paper looks at is lager yeast. It was shown a few years ago that lager yeast is a hybrid between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the relatively newly discovered wild species Saccharomyces eubayanus. S.eub was initially only found in South America, but has now also been found in Tibet.

So far the wild parent has gotten most of the attention, but in this paper we learn more about the S.cer parent. And the first thing we discover is that it was a Beer 1 yeast. So it seems that lager yeast came about through a domesticated brewing yeast mating with an S.eub yeast that somehow managed to get into the fermenting beer.

The other interesting thing is where lager yeast branches off: not from any of the big geographic subgroups of Beer 1: Belgian/German, UK, or US, but closer to the root. In fact, the closest neighbour is the little group of hefeweizen yeasts sitting near the root of Beer 1. Intriguingly, that's also where kveik branches off.

So what does this mean? Well, unfortunately we don't know the exact relationships between these three, because nobody has built a tree that has all three groups (lager parent, hefeweizen, kveik) in it. But it does seem like they all sit in the same part of the tree.

There could be several possible reasons for that:

- All three groups are hybrids (well, hefeweizen and kveik are "intraspecies hybrids", but whatever) and it could be that this causes them to group together genetically even without any historical relationship.

- They end up together because they all branched off from the rest of Beer 1 a long time ago.

- There really is a historical relationship between them. Lager and hefeweizen yeast both come from south Germany, so a historical relationship between those two would not really be surprising. For kveik to be related to them would be quite the surprise, though.

So which one of these is it? We don't know.

Another interesting thing is that lager yeast exists in two different types, known as Saaz (no relation to the hop) and Frohberg. Saaz is so named because it comes from the Bohemia region of the Czech Republic (where the town Žatec/Saaz is), while Frohberg comes from Bavaria. Most breweries today use Frohberg lager yeasts, but the Carlsberg yeast is Saaz. That's mildly surprising, because brewery founder J. C. Jacobsen acquired that yeast in Bavaria.

There's a lot more to learn from that paper, but I'm going to stop here, because this blog post is already more than long enough.

The big picture

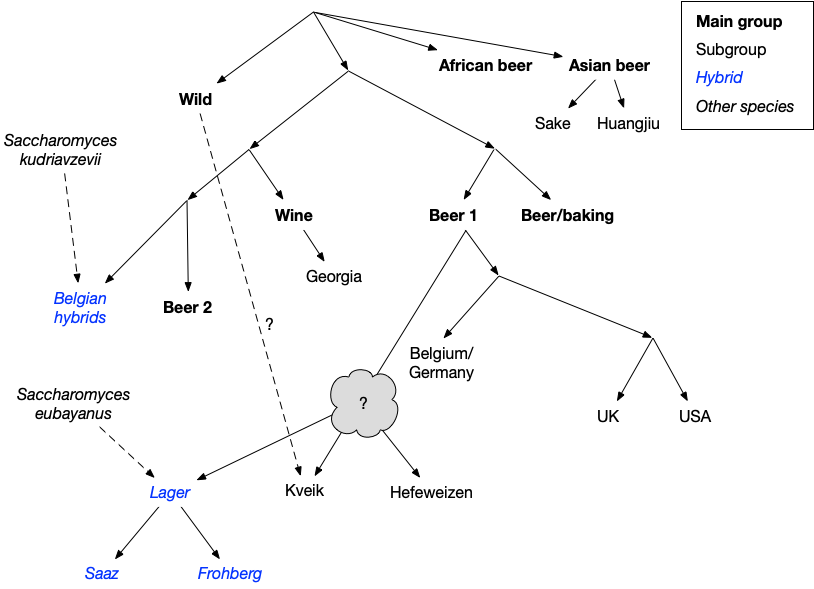

If we put all of this new information together, we can make a family tree for Saccharomyces cerevisiae that looks like this:

Simplified view of the full tree, drawn by yours truly. The cloud indicates the part that still hasn't been investigated properly. |

There are a few things that are not as tidy in that tree as they should be (such as the relationship between kveik, hefeweizen yeasts, and lager yeasts), but the big picture of how the various types of alcohol-producing yeasts are related to each other is becoming much clearer than it used to be.

Note that I left off some of the groups from the 1,011 study to make this more readable. I also renamed the "Mixed" group from Gallone 2016 to "Beer/baking", which was the name used in a later study.

Similar posts

Where kveik comes from

I've written before about the kveik research paper by Preiss, Tyrawa, and van der Merwe

Read | 2018-09-12 16:27

A family tree for brewer's yeast

I wrote a series of blog posts on the family tree of yeast, starting at the very top and continuing all the way down to the family of yeast species

Read | 2017-08-08 09:09

A family tree for kveik

In 2016 I was contacted by Canadian researcher Richard Preiss

Read | 2017-10-06 10:02

Comments

Nick - 2021-10-27 21:10:18

Absolutely fascinating, as per always. Thanks for the detailed explanation of this important research! Cheers from the UK

Alec Story - 2021-10-29 00:40:01

This is fantastic, thank you for the post. The huangjiu genetics is really interesting: I suspect most people are not familiar with the process since English-language sources are vanishingly rare, but it's been a thing I've been working on from historical recipes for a while and thought I'd leave a note.

We have recipes for this style of alcohol going back to 544 CE, and the ones I've looked at from that source, and a few later ones, follow a similar pattern: take a grain (usually wheat/barley, sometimes pulse) substrate, cook part of it, grind it all, optionally mix in some herbs, wet it, and make cakes of some thickness which you let cure under *very specific* conditions: recipes will go so far as to specify the kind of roof thatching you need to have. This is then used to inoculate the cooked grain with both yeast and the necessary Aspergillus and Rhizopus fungi to break down the starches.

So if we take that at face value, this should be a wild yeast! But seeing such a strong cluster makes that seem to not be the case. Either these yeasts were domesticated recently as people stopped following the traditional process recorded in the recipes, or something else is happening.

Lars Marius - 2021-10-29 09:24:41

@Alec: That's very interesting! In later production I know huangjiu brewers use a "yeast brick" that contains the mold and the yeast. But when they started using those I don't know. I guess it's possible that huangjiu yeast initially became domesticated much the same way as wine yeast: by hanging around in the environment in between brews, but getting into brews quite regularly.

Magnus Bark - 2021-10-29 09:42:00

As always, a very informative and fascinating peace of research. Thank you, Lars!

Kilian G - 2021-10-30 13:48:53

Where would Spanish wine strains fit in there? Specifically sherry strains that produce a pellicle although being Sacch strains (3 out of 4 are Saccharomyces Cerevisiae), I've always been intrigued by them

Rosly - 2021-11-01 13:32:30

@Lars: Thanks for another great article. The advances in yeast genomic ancestry of the past 5 years have been tremendous! You do great summaries of this important and interesting topic!

@ALec Story: I live and have brewed in Chengdu, Sichuan. I had a brewers dream of working with a traditional qingke drink from the Sichuan-Tibetan mountains called zajiu (咂酒,"straw alcohol", because the alcohol is drank with a straw right out of the fermentation pot--grain and all).

Your reference <take a grain (usually wheat/barley, sometimes pulse) substrate, cook part of it, grind it all, optionally mix in some herbs, wet it, and make cakes of some thickness which you let cure under *very specific* conditions> reminds me of some of the traditional "qu" that I got that is supposed to be better than new qu. I put qu in quotes because I was told it's not qu, haha.

It was made with a qingke powder/starch base and apparently some specific wild herb from the mountains. It was similar to what you referenced--only with small thorns! I was only able to do one test fermentation with it and unfortunately did not have time to monitor its flavor and basic characteristics throughout fermentation. I had decided to place the test vessels far from the actual brewery in an upstairs storage. I just know the final result was extremely sour. I am guessing there was many a wild and unique microflora.

I would love to know more about what you know about huangjiu/qu/microflora in China. It's been an interest of mine for a while. I've even attempted to isolate a wild yeast or two from the mountains here. Please contact me if you would like: rosly.schofield@gmail.com

Jamone Walker II - 2023-12-09 13:40:15

All yeast comes from nature, the wild… if you agree with that… and Jesus turning water to wine wasn’t a proper explanation for young hoodlums trying to swap sacramental wine jugs out for water, I’d probably try that trick too… from Chinese wine and wild funk to ales, lagers and wits, i appreciate them all but “the Belgian yeast” regardless the forefather or the country. I feel the majority of Belgian or Trappist yeasts came from a German hefe that saw some tribulations and environmental changes through stress and Temperature fluctuations, but I’m no geneticist, nor am i a historian of sugar eating co2 pooping, alcohol creating living organisms. Everything has its place and everyone is proud of their hard earned national concoctions, if you got an infected barrel and kept propagating that yeast because of well any fucking reason…. ( temp. Ingredients, bored with the local quaff) who knows why yeast changed and if it was environmental or they actually knew how to pick out the best parts…. As a Previous micro brewery, head brewer for almost 7-1/2 years. Iv seen damn near everything and my only heartfelt advice when it comes to yeast. Keep it clean. Keep it healthy, never think less is going to be enough…. And always know your off flavors and smells and never sell anything that’s not 100%. Even if you hate the style or the flavor…. As a brewer we know what beer shouldn’t taste or smell Like even if we won’t drink it ourselves. All the love to every fermentalist. - cheers! P.s. corporate beer sucks!