Where kveik comes from

Yeast ready for use, Sõru, Estonia |

I've written before about the kveik research paper by Preiss, Tyrawa, and van der Merwe. That paper was not accepted by the reviewers, who had a number of complaints. In addition to the serious complaints one reviewer, amusingly, had difficulty believing that farmhouse brewers ferment at 30-40C. Anyway, to get the paper accepted Richard and co went to work and expanded the research quite a lot, with help from Kristoffer Krogerus. That second round of research uncovered enough new information that I think it's worth doing a second blog post on the new, second edition of the paper. (Which now has been peer-reviewed and accepted.)

The first paper showed very clearly that kveik is a domesticated yeast. That is, a yeast that has been reused by humans for so long that it has changed into something that works better for humans and is adapted to the environment humans have created for it. So kveik is definitely not wild yeast. It's beer yeast. But what kind of beer yeast?

The family tree in the first version of the paper was based on DNA fingerprinting of a small part of the genome, and comparison with just a few other strains. That doesn't definitively answer whether kveik is a distinct subgroup of yeast or not. For that, you need full genome sequencing and a larger data set, which is expensive. However, they managed to get funding for it, so Kristoffer Krogerus sequenced 6 kveik strains and placed them into the big family tree for yeast.

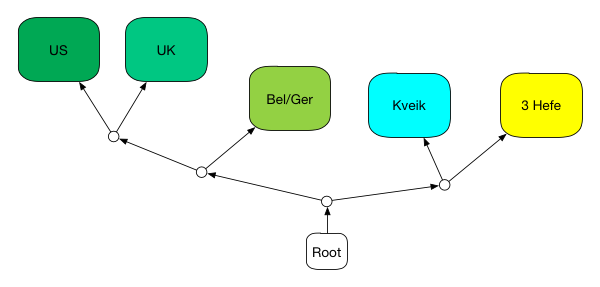

Substructure inside "Beer 1" |

The results were quite surprising: kveik belongs to Beer 1. This is the group that has Belgian/German strains on one side, and UK/US ones on the other. Kveik slots in near the root of Beer 1. You see the tree above: the basic division inside Beer 1 is between the US/UK/Bel/Ger yeasts on the one side, and kveik + 3 non-kveik yeasts on the other. (More on those below.)

So what does this tell us?

Obviously, kveik shares an origin with the biggest group of beer strains from commercial brewing. Almost certainly, Beer 1 started in continental Europe, and some of the strains were then taken across the channel to the UK, while others came to Norway. How and when that happened we don't know, but it's clearly a long time ago. Gallone et al calculated that the yeasts in Beer 1 began diverging around 1600 CE, but personally I consider that a low end estimate. That is, it probably can't have happened much more recently, but it may well have happened earlier. So I think we can confidently say kveik split off from the rest of Beer 1 centuries ago.

From the genetic signature of kveik (high heterozygosity) the researchers conclude that it is probably a mosaic (a kind of hybrid). This needs to be explained, I guess. Wild yeast can produce offspring by having two parents mate to make a child by mixing their DNA, like humans do. They can also produce new cells by simply "budding," letting a new cell form out of an existing cell. Budding is something humans (happily!) can't do. Brewer's yeast can usually only reproduce by budding, but there are some exceptions.

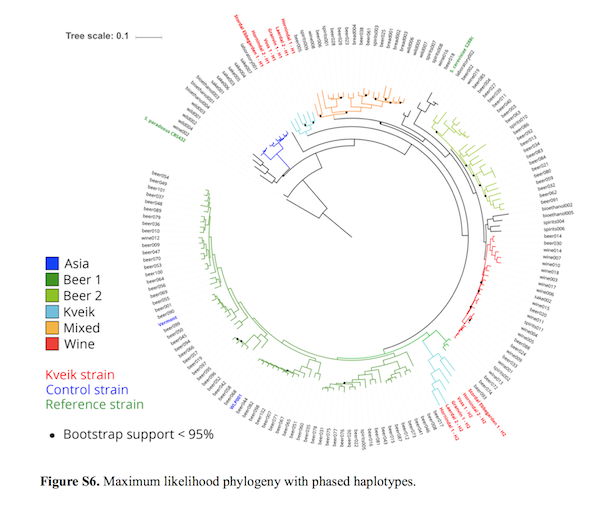

The family tree with the two halves of the genome (haplotypes) inserted separately. Look for the two sets of strain names in red around the outermost circle. |

What the researchers think is that at some point in the evolution of brewer's yeast, a yeast from Beer 1 mated with some other yeast from outside Beer 1, and that all the kveiks descend from this child. They used an algorithm to divide the genome into the genes they think came from one parent, and those they think came from the other. Making the tree again, but placing the two halves of the genomes into it separately, one half ends up in the same place in Beer 1, while another ends up in a kind of no-man's land not really close to anything. (See the two groups of red names in the diagram above.)

The researchers think this means that kveik was formed by a parent from very early Beer 1 mating with a wild yeast. This is not a firm research conclusion, however, just what looks most likely from the available data. Since all six kveiks show the same signature, very likely this hybridization happened a long time ago. Whether it happened on the continent or in Norway we have no idea.

(This hybridization event, by the way, if it happened, is similar to how lager yeast formed, by normal brewer's yeast mating with a wild yeast from a different, cold-tolerant species. In the case of kveik, both parents were Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but from very different populations within the species.)

But what about those three non-kveik yeasts that are their closest neighbours? Those are three hefeweizen yeasts, intriguingly. Unfortunately, that result is probably because both are mosaics (within-species hybrids) and that similarity is what causes them to cluster together, rather than any historical relationship. Probably. It's a tantalizing fact, though, that the two most aromatic types of beer yeast end up right next to each other. (I'm not counting Brettanomyces, because it's a completely different genus, group of species.)

Idun Blå, Norwegian bread yeast |

One thing the reviewers questioned was whether kveik might be bread yeast rather than real farmhouse yeast, since the sahti and gotlandsdricke brewers are all using bread yeast. The researchers fingerprinted the Norwegian baking yeast Idun Blå, and it ends up in a completely different place in the tree. So kveik is definitely not related to Idun Blå.

To summarize, kveik is definitely domesticated brewer's yeast, relatively closely related to continental beer yeast. It's probably a hybrid between those and a wild yeast that was then domesticated further over centuries.

The big lesson we learned from the Gallone et al 2016 paper was that most brewing yeasts are related, which shows that properly domesticated yeast must have been valuable thing that brewers took good care of, and shared with each other. That's how a single family of yeast managed to spread out from Belgium and Germany to the UK, and from the UK to the US. Other, similar, family tree research projects have found similar results, so there's every reason to be believe this is correct.

Kveik getting started, Norwegian farmhouse ale festival, Hornindal |

This paper brings that out even more clearly. Even in Western Norway it turns out brewers are still using descendants of this same Beer 1 family. The fact that all the kveiks, from Hardanger in the south to Sykkylven in the north, are related to each other shows both that brewers have been sharing their yeasts, and also that they have been very careful to preserve their domesticated yeast. One also gets the impression that there weren't that many options: this single type of yeast was apparently preferred over all alternatives. So maybe domestication of yeast didn't happen that many times?

It's worth repeating that the one non-Norwegian farmhouse yeast that was included (#16 Simonaitis, from Lithuania) is not related to the kveiks. So there are farmhouse yeasts that are not kveik. This leads us to the still open questions. We've now collected farmhouse yeast from eastern Norway, more from Lithuania, from Latvia, and from Russia. Where do those fit? Are the eastern farmhouse yeasts a separate group that ferments hot and fast? Is eastern Norwegian farmhouse yeast kveik, or something else? We don't know yet.

But since two of the six known Lithuanian yeasts belong to completely different species my guess is that the non-kveiks don't all belong to a single family. But we won't know for certain until the researchers do some more work.

Acknowledgements

Big thanks to Richard Preiss and Kristoffer Krogerus for taking the time to answer my questions on how to understand the results.

Update

The best family tree including kveik can be found here.

It was made by Kristoffer Krogerus and published in this blog post.

Similar posts

A family tree for kveik

In 2016 I was contacted by Canadian researcher Richard Preiss

Read | 2017-10-06 10:02

The Yeast Family Tree Grows

A few years ago I wrote about the groundbreaking study (Gallone et al 2016) that for the first time gave us an idea of how the different types of brewers yeast are related to each other

Read | 2021-10-26 10:39

A family tree for brewer's yeast

I wrote a series of blog posts on the family tree of yeast, starting at the very top and continuing all the way down to the family of yeast species

Read | 2017-08-08 09:09

Comments

Robert Manktelow - 2018-09-12 21:31:51

Great to see this Lars. Could you advise if the kveik as per the registry was used in the study, and if so which ones. So for example, is Voss 1 Sigmund Gjernes kveik, or another Voss Kveik? Is the Stordal Ebbegarden that of Jens Aage Øvrebust?

Lars Marius Garshol - 2018-09-13 06:32:49

@Robert: Good point. In the supplementary material, page 10/14, there is a table showing more detail on the cultures. The numbers, like Voss 1 and Voss 2, refer to specific strains inside a culture. The registry only has the mixed cultures (which would be Voss 1, Voss 2, and whatever else is in the culture).

Marco - 2018-09-13 15:21:58

Out of curiosity, are there any well known beer 2 strains?

Lars Marius Garshol - 2018-09-16 09:43:04

@Marco: Kristoffer Krogerus and the anonymous qq have done a fantastic piece of detective work, and produced a version of the tree with meaningful names: http://beer.suregork.com/?p=3919

The White Labs Belgian and French saison yeasts all seem to be Beer 2, and also some British strains. See the diagrams there and you can figure it out.

qq - 2018-10-18 14:06:45

Ach, sorry, I've had this page open for weeks now, I meant to reply earlier.

@Marco - As Lars says, Beer 2 are typically saison yeasts. They're closely related to the wine yeasts, so you get an idea of them being used seasonally, which means they experience far fewer generations per year compared to the full-time "brewery" yeasts of Beer1 and so have "primitive" characteristics like being POF+ (producing the phenolics that give you "Belgian-ness"). So Beer2 yeast show less signs of domestication, like cats, whereas Beer1 strains are more domesticated, like dogs.

Congratulations and thanks to all involved in this work though, not least the funding bodies that allow it all to happen in the first place! It's fascinating to see that explosion of yeast happening in the Middle Ages, which looks like a combination of an efficient transport network across the North Sea and Baltic, and something "new" that was so much better than what came before that it pushed out whatever people had been using before.

As I've said before, that all sounds like the Hanseatic League and hopped beer, in particular the beer with enough alpha to allow long-distance transport which seems to have emerged in places like Liege towards the end of the Hansa's golden age. We've plenty of more recent examples of a "special" yeast that is associated with a hot new style of beer and travels with it, whether for lager or how Conan was the "magic" yeast in the early years of New England IPAs.

Hope you get funding to study the Baltic yeasts! For those that haven't seen, the Yeast Bay (no affiliation) are now offering a Simonaitis strain in their beta programme.

qq - 2018-10-18 16:32:57

PS I meant to add - some of the Beer2's are a small group of British yeasts mostly from Yorkshire - it seems the Yorkshire square system is a technological fix to make saison-like yeast behave in a more British fashion. WLP037 Yorkshire and WLP038 Manchester are POF+ examples, WLP026 is an intriguing example that is POF+. Perhaps the best commercial example where you can pick up a hint of phenolics is Harvey's Best, which uses a yeast originally from John Smith. But even that is pretty subtle.

Per Christian - 2018-10-25 20:42:01

Thank you very much for your work Lars Marius, I really appreciate your research, curiosity and persistence.

Reading your comment about Idun Blå, and after sampling the (often rather lovely) beers made with Idun Blå at Norsk Konnjølfestival this year I wonder whether this bread yeast culture is a static thing.

Roar Sandvolden's talk on brewing in Stjørdal included a point that the brewers in that region migrated to Idun Blå, and he saw it as unlikely that convenience could be the only reason. His argument (as I understood it), is that this commercial bread yeast must somehow have been better than the alternatives to be able to supplant them so completely.

So my next question is what goes into Idun Blå, for it to be able to supplant a traditional yeast culture in a region with a lively brewing tradition? Where did that culture come from, what properties does it have, and how is it maintained?

A quick google search indicates that whatever Idun Blå was before 2005 probably changed when Orkla moved decided to move Idun's production of yeast to Jästbolaget AB in Sweden.

Stray thought. Love the blog, and your book on Gårdsøl.

Per Christian

Lars Marius Garshol - 2018-10-26 06:39:48

@qq: We don't know that the explosion happened that quickly, or that it happened in the Middle Ages. The age calculation in Gallone et al basically is not trustworthy (because that method doesn't work, not because they cheated or anything). We don't really know much about the timing.

What you're saying about Yorkshire is interesting!

Lars Marius Garshol - 2018-10-26 06:47:21

@Per Christian: Thank you! This thing about the bread yeasts is very interesting. Lots of different bread yeasts turn out to be surprisingly good at brewing beer. In fact, they behave exactly like farmhouse yeasts. They handle very hot fermentation, ferment very fast, good attenuation, not phenolic, clean, and fruity. So one really does have to wonder where they came from.

And basically there are only two possibilities for where they can have come from: either from brewing, or from sourdough. But I don't really know much more yet. The yeast companies don't seem to know (or care) where the yeast originally came from, and they've typically been using their strains for so long that nobody in the companies remember.

But I don't buy the argument that Idun Blå must necessarily be superior to the yeast they used in Stjørdal before. People have ditched kveik in parts of Hardanger in favour of Idun Blå. Idun Blå is a good yeast, but not better than kveik. The same thing happened in Sogn, too.

According to Räsänen, until the early 20th century hardly anyone bought yeast because the farmhouse yeast was considered better. And yet one century later the farmhouse yeast is gone in favour of the bread yeast.

So personally I really do believe that convenience, and a feeling that perhaps this old-fashioned home yeast is not as good as modern shop yeast, could well be what drove the transition. Idun Blå is not necessarily better than what they had.

qq - 2018-10-26 15:36:31

Arggh - I meant to say "WLP026 is an intriguing example that is POF-", not POF+!!!! It's not something that anyone's paid much attention to, and I'm still waiting for it to leave the Vault, but it hints that we should perhaps view the Burton Union as an evolved Yorkshire square in technological and yeast terms.

@Lars I don't buy the reliance on US timings to calibrate their chronology - but at the same time it's not going to be wildly out as it's constrained by other factors like the evolution of lager which also puts some limits on it. It could be 200 years out but it's very unlikely to be 2000 years out. And even if there was no calibration, the overall shape of the tree gives you some idea. The fact that there was an initial radiation followed by a significant time where eg UK/kveik/Rhine-ish families evolved in relative isolation just feels like it's reflecting an initial spread in the Middle Ages.

Interesting about bread yeast - the Gallone paper sequenced a couple and they were all from a very narrow group in the Mixed grouping. 1002 Genomes sequenced nearly 40 and most were also spread around the Mixed grouping with some in Mosaic Region 3. I've not seen anything about their POF status though, I thought that in general they were mostly POF+ as there was no reason to select for POFness in bread, so POF- ones are likely beer yeasts that have ended up being used for bread?

Martyn Cornell - 2018-11-15 23:26:52

"we should perhaps view the Burton Union as an evolved Yorkshire square in technological and yeast terms" - the Burton Union system is an evolution of the earlier "dropping into casks" system, where the initial fermentation in a large vessel was followed by transferring the still-fermenting wort into large casks for "cleansing". All Burton Unions did was automate some of the drudgery of the "dropping into casks" system, which required a man with a can to top up the casks as wort and yeast flowed out. The "ponto" system was a similar set-up. Yorkshire Squares were a parallel development, a sort of overblown or giant cask with the "yeast trough" sitting on top of the vessel in which the fermentation was taking place, "cousins" to Burton Unions, rather than "parents".